5 Week 5

5.1 Setting Up

# Load packages

library(skimr)

library(gt)

library(gtsummary)

library(epiR)

library(broom)

library(pROC)

library(gmodels)

library(survival)

library(here)

library(tidyverse)

# Load data necessary to run Week 5 examples

lesson2b <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 2", "lesson2b.rds"))

lesson3d <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 3", "lesson3d.rds"))

lesson4d <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 4", "lesson4d.rds"))

lesson5a <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5a.rds"))

example5a <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "example5a.rds"))

example5b <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "example5b.rds"))5.2 R Instructions

5.2.1 Correlation

Correlating two or more variables is very easy: just use the cor function and then the dataset and selected variables.

For example, if you use the lesson2b dataset and correlate the first four pain scores, you get the following table:

# Display the correlation between variables l01, l02, l03 and l04

cor(lesson2b %>% select(l01, l02, l03, l04))## l01 l02 l03 l04

## l01 1.0000000 0.7900984 0.6270860 0.5395075

## l02 0.7900984 1.0000000 0.8145025 0.7148299

## l03 0.6270860 0.8145025 1.0000000 0.8383224

## l04 0.5395075 0.7148299 0.8383224 1.0000000This shows, for example, that the correlation between l01 and l02 is 0.79 and the correlation between l02 and l04 is 0.71. From the table you can easily see that pain scores taken on consecutive days are more strongly correlated than those taken two or three days apart.

If the data are skewed, you can try a regression based on ranks, what is known as Spearman’s rank correlation. What you’d type is the same as above, but adding the option method = "spearman".

# Calculate the Spearman correlation for skewed data

cor(lesson2b %>% select(l01, l02, l03, l04), method = "spearman")## l01 l02 l03 l04

## l01 1.0000000 0.7799856 0.6220233 0.5443327

## l02 0.7799856 1.0000000 0.8126008 0.7220277

## l03 0.6220233 0.8126008 1.0000000 0.8324906

## l04 0.5443327 0.7220277 0.8324906 1.00000005.2.2 Linear regression

Linear regression is when you try to predict a continuous variable. The function to use is lm.

The first variable is the dependent variable (e.g. blood pressure) and must be continuous. The other variables are the predictor variables and can be binary or continuous: in some cases you can use ordinal variables but you have to be careful. We’ll deal with categorical variables later in the course. The dependent and predictor variables are separated by a “~”, and multiple predictor variables are separated by “+”.

Let’s use the data from lesson3d as an example dataset. We want to see if we can predict a patient’s range of motion after treatment (variable a) in terms of their age, sex and pre-treatment range of motion (variable b).

# Linear regression model for a, predictors are sex, age and b

lm(a ~ sex + age + b, data = lesson3d)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = a ~ sex + age + b, data = lesson3d)

##

## Coefficients:

## (Intercept) sex age b

## 138.7336 2.8524 -0.4359 0.6692This gives you the very basic information from the regression, but you can get more information using the summary function:

# Save out linear regression model

rom_model <- lm(a ~ sex + age + b, data = lesson3d)

# Show additional model results

summary(rom_model)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = a ~ sex + age + b, data = lesson3d)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -60.135 -11.943 3.238 14.523 47.732

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 138.73363 29.50514 4.702 5.40e-05 ***

## sex 2.85241 10.25817 0.278 0.783

## age -0.43589 0.27770 -1.570 0.127

## b 0.66924 0.07816 8.563 1.49e-09 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 25.29 on 30 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.7475, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7222

## F-statistic: 29.6 on 3 and 30 DF, p-value: 4.241e-09The first column of numbers listed under “Coefficients” are the coefficients. You can interpret this as follows: start with 138.7 degrees of range of motion (the intercept or constant). Then add 2.85 if the patient is a woman, and take away 0.436 degrees for every year of age. Finally, add 0.669 degrees for every degree of range of motion the patient had before the trial.

Let’s take a single patient: a 54 year old woman with a range of motion of 301 before treatment. Her predicted range of motion afterwards is 138.7 + 2.85 - 0.436*54 + 0.669*301 = 319.5. Her actual figure was 325, so we predicted quite well for this patient. You can get R to do this automatically using the augment function from the {broom} package.

# The "augment" function creates a dataset of all patients included in the model

# and all variables included in the model, as well as the predictions

lesson3d_pred <- augment(rom_model)

# Print out new dataset to show output from "augment"

# The ".fitted" column is your prediction

# You can ignore all columns to the right of ".fitted"

lesson3d_pred## # A tibble: 34 × 10

## a sex age b .fitted .resid .hat .sigma .cooksd .std.resid

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 247 1 24 263 307. -60.1 0.201 22.5 0.447 -2.66

## 2 324 0 73 339 334. -9.79 0.129 25.7 0.00638 -0.415

## 3 351 0 40 361 363. -11.9 0.0947 25.6 0.00639 -0.494

## 4 232 0 74 234 263. -31.1 0.113 25.0 0.0540 -1.30

## 5 328 0 51 329 337. -8.68 0.0542 25.7 0.00178 -0.353

## 6 380 0 26 376 379. 0.966 0.164 25.7 0.0000853 0.0417

## 7 302 0 54 297 314. -12.0 0.0411 25.6 0.00250 -0.483

## 8 254 0 39 249 288. -34.4 0.0832 24.8 0.0457 -1.42

## 9 250 1 65 244 277. -26.5 0.131 25.2 0.0480 -1.13

## 10 252 0 81 246 268. -16.1 0.144 25.5 0.0197 -0.686

## # ℹ 24 more rowsTo get the number of observations, coefficients, 95% confidence interval and p-values printed in a table for all covariates, you can use the tbl_regression function from the {gtsummary} package:

| Characteristic | Beta | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1=female | 2.9 | -18, 24 | 0.8 |

| age | -0.44 | -1.0, 0.13 | 0.13 |

| range of motion before acupuncture | 0.67 | 0.51, 0.83 | <0.001 |

| Abbreviation: CI = Confidence Interval | |||

For example, for sex, the 95% CI is -18 to 24, meaning that women might plausibly have a range of motion anywhere from 18 degrees less than men to 24 degrees more. In short, we don’t have any strong evidence that sex has an effect on range of motion at all and we can see this reflected in the p-value, p=0.8. There are 34 patients included in this model. You can determine the number of observations included in the model using the nobs() function, or you can update the table to include this number in the header.

## [1] 34# By default, the number of observations is not shown in "tbl_regression"

# You can use the code below to print the number of observations in the table header

tbl_regression(rom_model) %>%

modify_header(

label = "**Characteristic (N = {N})**"

)| Characteristic (N = 34) | Beta | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1=female | 2.9 | -18, 24 | 0.8 |

| age | -0.44 | -1.0, 0.13 | 0.13 |

| range of motion before acupuncture | 0.67 | 0.51, 0.83 | <0.001 |

| Abbreviation: CI = Confidence Interval | |||

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = a ~ sex + age + b, data = lesson3d)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -60.135 -11.943 3.238 14.523 47.732

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 138.73363 29.50514 4.702 5.40e-05 ***

## sex 2.85241 10.25817 0.278 0.783

## age -0.43589 0.27770 -1.570 0.127

## b 0.66924 0.07816 8.563 1.49e-09 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 25.29 on 30 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.7475, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7222

## F-statistic: 29.6 on 3 and 30 DF, p-value: 4.241e-09At the bottom of the summary readout there are a few miscellaneous tidbits:

The “p-value” next to the “F-statistic” on the last line tells you whether, as a whole, your model, including the constant and three variables, is a statistically significant predictor.

The “Multiple R-squared” value (often referred to as just “r squared”) tells you how good a predictor it is on a scale from 0 to 1. We’ll discuss the meaning of r squared in more detail, but it is defined as the proportion of variation that you can explain using your model.

5.2.3 Graphing the data

Graphing the data is done using the ggplot function from the {ggplot2} package. In short, the main inputs for the ggplot function are your dataset, the x variable and the y variable. You can then create a number of different plots using this data.

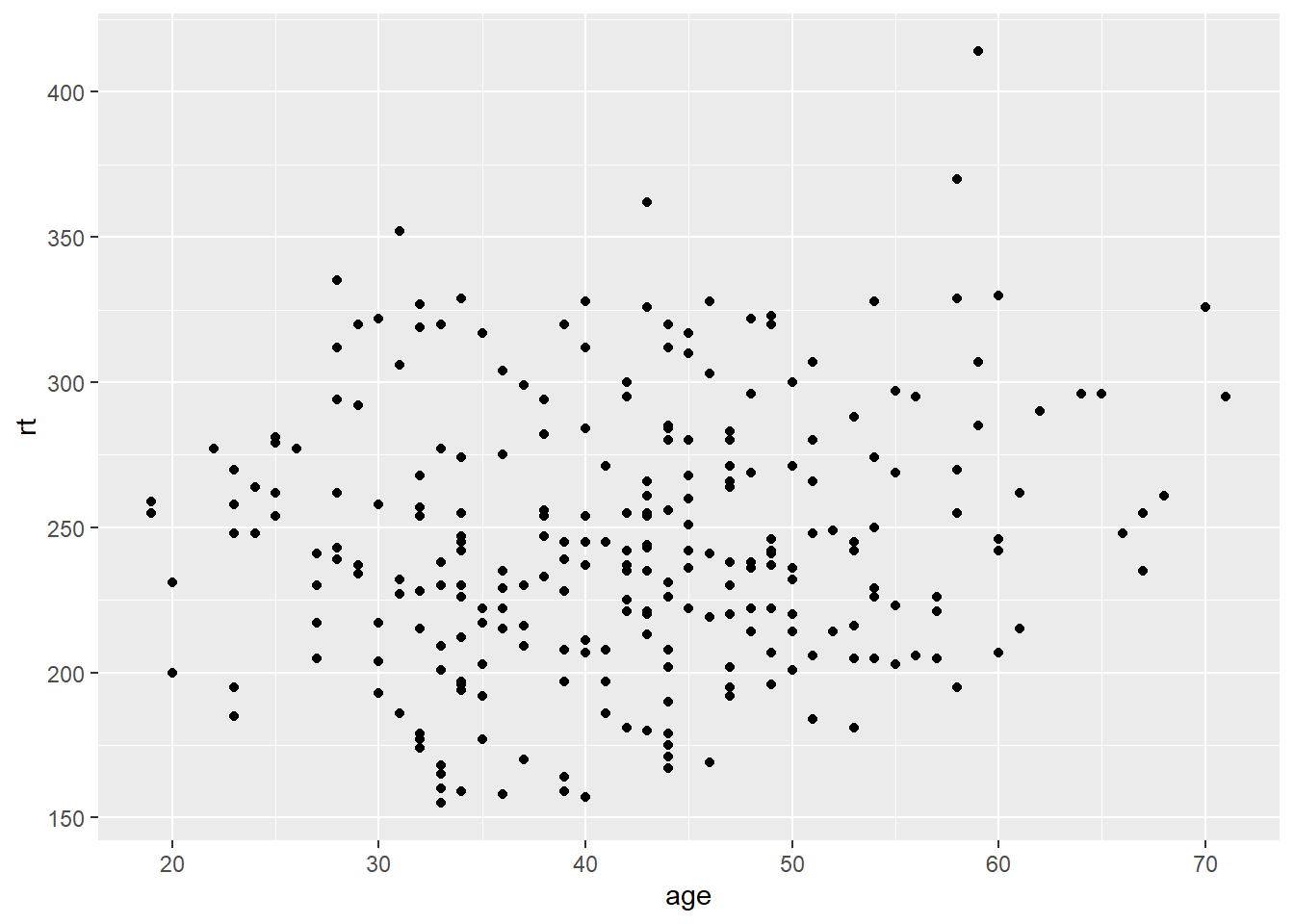

To create a scatterplot, the geom_point function is added to the ggplot function:

# Create a scatterplot of race time by age

ggplot(data = lesson5a,

aes(x = age, y = rt)) +

geom_point()

This scatterplot from the lesson5a data shows race time and age for every runner in the study. This is a useful way of getting a feel for the data before you start.

5.2.4 Logistic regression

Logistic regression is used when the variable you wish to predict is binary (e.g. relapsed or not). The function to use is glm, with the option family = "binomial" to indicate that our outcome variable is binary.

Again, the first variable is the dependent variable (e.g. hypertension) and must be binary. The other variables are the predictor variables and can be binary or continuous: again, in some cases you can use ordinal variables but you have to be careful. The variables are entered into the glm function the same way as the lm function (dependent ~ predictor1 + predictor2 + …).

We’ll use the dataset lesson4d as an example.

# Create a logistic regression model for response, predictors are age, sex and group

response_model <- glm(response ~ age + sex + group, data = lesson4d, family = "binomial")

# Look at additional model results

summary(response_model)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = response ~ age + sex + group, family = "binomial",

## data = lesson4d)

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 0.967546 0.447037 2.164 0.0304 *

## age -0.023270 0.009807 -2.373 0.0177 *

## sex -0.180196 0.234045 -0.770 0.4413

## group -0.318300 0.205037 -1.552 0.1206

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 546.87 on 397 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 538.18 on 394 degrees of freedom

## (2 observations deleted due to missingness)

## AIC: 546.18

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4By default, R gives the coefficients in logits for logistic regression models. To easily see the coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for all covariates as odds ratio, we can again use the tbl_regression function. In this case, we use the option exponentiate = TRUE, which indicates that odds ratios (not logits) should be presented. (You can also use this function to see the formatted logit results by using the exponentiate = FALSE option.)

# Create logistic regression model

glm(response ~ age + sex + group, data = lesson4d, family = "binomial") %>%

# Pass to tbl_regression to show formatted table with odds ratios

tbl_regression(exponentiate = TRUE)| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| age | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | 0.018 |

| 1 if woman, 0 if man | 0.84 | 0.53, 1.32 | 0.4 |

| 1 if b, 0 if a | 0.73 | 0.49, 1.09 | 0.12 |

| Abbreviations: CI = Confidence Interval, OR = Odds Ratio | |||

The key things here are the odds ratios: you can say that the odds of response is multiplied by 0.98 for a one year increase in age; that women have an odds of response 0.84 of that for the men, though this is not statistically significant, and that response is lower in group 1, with an odds of 0.73 (you would also cite the p-value and 95% CIs).

The problem here is that you can’t use any of these data to work out an individual patient’s chance of response. Now you can get R to do this for you using the augment function. For a binary outcome, you need to specify type.predict = "response" as an option so that you will get predicted probabilities (not log odds).

# Get predictions from logistic regression model

# type.predict = "response" gives predicted probabilities

lesson4d_pred <-

augment(response_model, type.predict = "response")

# Look at the dataset containing predicted probabilities (.fitted variable)

# You can ignore all columns to the right of ".fitted"

lesson4d_pred## # A tibble: 398 × 11

## .rownames response age sex group .fitted .resid .hat .sigma .cooksd

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 1 47 0 0 0.469 1.23 0.00612 1.17 0.00176

## 2 2 0 47 0 0 0.469 -1.12 0.00612 1.17 0.00137

## 3 3 1 25 0 0 0.595 1.02 0.0129 1.17 0.00226

## 4 4 0 53 0 1 0.358 -0.941 0.00841 1.17 0.00119

## 5 5 1 64 0 0 0.372 1.41 0.0154 1.17 0.00669

## 6 6 0 50 0 1 0.374 -0.968 0.00738 1.17 0.00112

## 7 7 1 34 0 1 0.465 1.24 0.00838 1.17 0.00245

## 8 8 0 68 0 1 0.282 -0.814 0.0178 1.17 0.00182

## 9 9 0 49 0 0 0.457 -1.11 0.00659 1.17 0.00140

## 10 10 0 44 0 1 0.407 -1.02 0.00641 1.17 0.00112

## # ℹ 388 more rows

## # ℹ 1 more variable: .std.resid <dbl>Note: The lesson4d_pred dataset includes 398 patients. If you look at the table above, you will see at the top that all 398 patients were included in the model. Any patients who are missing data for the outcome or any predictors will be excluded from the model, and will not be included in the predicted dataset.

If you want to look at calculating predictions from logistic regression in more detail, you’ll need logit (see below).

One thing to be careful about is categorical variables. Imagine that you had the patients age and cancer stage (1, 2, 3 or 4) and wanted to know whether they recurred. If you tried glm(recurrence ~ age + stage, ...), then stage would be treated as if the increase in risk going from stage 1 to 2 was exactly the same as that going from 2 to 3 and 3 to 4. To tell R that it is a categorical variable, you need to use the factor function with the categorical variable:

# Create a model for recurrence using the categorical variable "stage"

recurrence_model <-

glm(recurrence ~ age + factor(stage), data = example5a, family = "binomial")

# Show the results of this model

summary(recurrence_model)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = recurrence ~ age + factor(stage), family = "binomial",

## data = example5a)

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -3.410438 0.309203 -11.030 < 2e-16 ***

## age 0.042057 0.005531 7.604 2.87e-14 ***

## factor(stage)2 0.996064 0.152510 6.531 6.53e-11 ***

## factor(stage)3 1.655345 0.260107 6.364 1.96e-10 ***

## factor(stage)4 1.771858 0.292687 6.054 1.41e-09 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 1369.7 on 1063 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 1212.9 on 1059 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 1222.9

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 3| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| age | 1.04 | 1.03, 1.05 | <0.001 |

| factor(stage) | |||

| 1 | — | — | |

| 2 | 2.71 | 2.01, 3.66 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 5.23 | 3.16, 8.79 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 5.88 | 3.34, 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Abbreviations: CI = Confidence Interval, OR = Odds Ratio | |||

What you can see here is that stage is broken into categories. The odds ratio is given comparing each stage to stage 1 (the reference). So the odds of recurrence is 2.71 higher for stage 2 compared to stage 1, 5.23 for stage 3 compared to stage 1 and 5.88 for stage 4 compared to stage 1.

For keen students only!

Here we look at our “response” model on the logit scale.

##

## Call:

## glm(formula = response ~ age + sex + group, family = "binomial",

## data = lesson4d)

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 0.967546 0.447037 2.164 0.0304 *

## age -0.023270 0.009807 -2.373 0.0177 *

## sex -0.180196 0.234045 -0.770 0.4413

## group -0.318300 0.205037 -1.552 0.1206

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 546.87 on 397 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 538.18 on 394 degrees of freedom

## (2 observations deleted due to missingness)

## AIC: 546.18

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4Firstly, note that the p-values are the same, what differs is the coefficients. Now if you are really smart, you’ll notice that the coefficient is the natural log of the odds ratios above. You can use the coefficients to work out an individual’s probability of response. We start with the constant, and subtract 0.0233 for each year of age and then subtract an additional 0.18 if a woman and 0.318 if in group 1. Call this number “l” for the log of the odds. The probability is el / (1 + el). Take a 53 year old man on regimen b (group 1): l = 0.9675 + -0.0233*53 + -0.318, gives -0.5841.

To convert, type exp(-0.5841) / (exp(-0.5841)+1) to get a probability of 35.8%.

5.2.5 Getting the area-under-the-curve

Using regression models is a way to try to predict outcome based on the data we have. After we’ve created a model, we want to know - is the prediction from this model any good? One way to do this is by assessing the discrimination. For logistic regression, where we have a binary endpoint, discrimination tells us how well the model distinguishes between patients who have the event and patients who do not have the event. Discrimination is measured using the area-under-the-curve (AUC) and varies between 0.5 (a coin flip) and 1 (perfect discrimination).

Imagine that you wanted to know how well a blood marker predicted cancer. Note that the blood marker could be continuous (e.g. ng/ml) or binary (positive or negative such as in a test for circulating tumor cells), it doesn’t matter for our purposes.

##

## Call:

## roc.formula(formula = cancer ~ marker, data = example5b)

##

## Data: marker in 1865 controls (cancer 0) < 635 cases (cancer 1).

## Area under the curve: 0.8143So the marker has an area under the curve of 0.814. The roc function from the {pROC} package is particularly useful if you want to know the area-under-the-curve with and without a marker.

For instance, the code below could tell you how much the area-under-the-curve increases when you add a new marker to a model to predict cancer that already includes age.

First, get the AUC for the model with age only:

##

## Call:

## roc.formula(formula = cancer ~ age, data = example5b)

##

## Data: age in 1865 controls (cancer 0) < 635 cases (cancer 1).

## Area under the curve: 0.6354The roc function can only take one predictor variable. For a univariate model, such as the model assessing age above, you can put “age” directly into the roc function. If you want to assess a model with multiple variables, you can use the predicted value:

# Create the multivariable model

marker_model <- glm(cancer ~ age + marker, data = example5b, family = "binomial")

# Use "augment" to get predicted probability

marker_pred <- augment(marker_model, type.predict = "response")Now, calculate the AUC for the model with age and the marker by using the predicted probability based on the multivariable model:

##

## Call:

## roc.formula(formula = cancer ~ .fitted, data = marker_pred)

##

## Data: .fitted in 1865 controls (cancer 0) < 635 cases (cancer 1).

## Area under the curve: 0.7996The AUC for the model including both age and the marker value is higher than for age alone, so we can conclude that the marker adds important predictiveness to age.

5.3 Assignments

# Copy and paste this code to load the data for week 5 assignments

lesson5a <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5a.rds"))

lesson5b <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5b.rds"))

lesson5c <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5c.rds"))

lesson5d <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5d.rds"))

lesson5e <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5e.rds"))

lesson5f <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5f.rds"))

lesson5g <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5g.rds"))

lesson5h <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5h.rds"))

lesson5i <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5i.rds"))Regression is a very important part of statistics: I probably do more regressions that any other type of analysis, apart from than calculating basic summary data such as medians, means and proportions. So, I’ve given you lots of possibilities here. I’ve coded them: you really should try to do the bold ones, do those in italics if you can, and if you get to the rest, well, the more the merrier. The reason I have included all this is so I can go over it in class.

lesson5a: These are data from marathon runners (again). Which of the following is associated with how fast runners complete the marathon: age, sex, training miles, weight?

lesson5b: These are data on patients with a disease that predisposes them to cancer. The disease causes precancerous lesions that can be surgically removed. A group of recently removed lesions are analyzed for a specific mutation. Does how long a patient has had the disease affect the chance that a new lesion will have a mutation?

lesson5c: These are data from Canadian provinces giving population, unemployment rates and male and female life expectancy. Which of these variables are associated?

lesson5d: These are data from mice inoculated with tumor cells and then treated with different doses of a drug. The growth rate of each animal’s tumor is then calculated. Is this drug effective?

lesson5e: These are data from a study of the use of complementary medicine (e.g. massage) by UK breast cancer patients. There are data for the women’s age, time since diagnosis, presence of distant metastases, use of complementary medicine before diagnosis, whether they received a qualification after high school, the age they left education, whether usual employment is a manual trade, socioeconomic status. What predicts use of complementary medicine by women with breast cancer?

lesson5f: These are the distance records for Frisbee for various ages in males. What is the relationship between age and how far a man can throw a Frisbee?

lesson5g: You’ve seen this dataset before. Patients with lung cancer are randomized to receive either chemotherapy regime a or b and assessed for tumor response. We know there is no statistically significant difference between regimens (you can test this if you like). However, do the treatments work differently depending on sex? Do they work differently by age?

lesson5h: PSA is used to screen for prostate cancer. In this dataset, the researchers are looking at various forms of PSA (e.g. “nicked” PSA). What variables should be used to try to predict cancer? How accurate would this test be? (NOTE: these data were taken from a real dataset, but I played around with them a bit, so please don’t draw any conclusions about PSA testing from this assignment).

lesson5i: This is a randomized trial of behavioral therapy in cancer patients with depressed mood (note that higher score means better mood). Patients are randomized to no treatment (group 1), informal contact with a volunteer (group 2) or behavior therapy with a trained therapist (group 3). What would you conclude about the effectiveness of these treatments?