9 Assignment Answers

9.1 Week 1

# Week 1: load packages

library(skimr)

library(gt)

library(gtsummary)

library(epiR)

library(broom)

library(pROC)

library(gmodels)

library(survival)

library(here)

library(tidyverse)

# Week 1: load data

lesson1a <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 1", "lesson1a.rds"))9.1.1 lesson1a

This is data for 386 patients undergoing surgery. What type of data (e.g. continuous, binary, ordinal, nonsense) are each of the variables?

The dataset has 11 variables:

- “id” is clearly a hospital record number. It doesn’t matter what type of variable it is, because you only want to know the type of variable in order to summarize or analyze data, and you’d never want to analyze or summarize patient id.

- “sex” is a binary variable

- “age” is continuous

- “p1”, “p2”, “p3”, “p4” are the pain scores after surgery. They only take integer values between 0 and 6. They would therefore typically regarded as categorical, and because they are clearly ordered (i.e. pain score of 6 is higher than one of 4) these variables can be described are ordinal. However, many statisticians, myself included, would think it perfectly reasonable to treat these variables as continuous.

- “t”: total pain score takes on values between 0 and 24 and can thus be considered continuous

- “x”, “y” and “z”: should you attempt to summarize a variable if you don’t know what it is? It is obvious for y, this is some kind of hospital location, and is a categorical variable. But what about x and z? As it happens, z looks ordinal but isn’t: it is blood group coded 1=o, 2=a, 3=b, 4=ab.

9.2 Week 2

# Week 2: load packages

library(skimr)

library(gt)

library(gtsummary)

library(epiR)

library(broom)

library(pROC)

library(gmodels)

library(survival)

library(here)

library(tidyverse)

# Week 2: load data

lesson2a <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 2", "lesson2a.rds"))

lesson2b <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 2", "lesson2b.rds"))

lesson2c <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 2", "lesson2c.rds"))

lesson2d <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 2", "lesson2d.rds"))

lesson2e <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 2", "lesson2e.rds"))9.2.1 lesson2a

This is data from marathon runners: summarize age, sex, race time in minutes (i.e. how long it took them to complete the race) and favorite running shoe.

Age is continuous and normally distributed (look at a graph or look at the centiles) and so it wouldn’t be unreasonable to describe age in terms of mean and standard deviation (SD) by using lesson2a %>% skim(age): mean of 42 years, SD of 10.2. By the way, don’t just copy the readout from R: this would give mean age as 42.43 and implies we are interested in age within a few days.

Sex is binary: use tbl_summary(lesson2a %>% select(sex)) to get percentages. But note that the person who prepared the data didn’t state how the variable was coded (someone with sex=1 is a woman or a man?). Now what you should do in this situation is ask, but here is another alternative:

| Name | Piped data |

| Number of rows | 98 |

| Number of columns | 6 |

| _______________________ | |

| Column type frequency: | |

| numeric | 1 |

| ________________________ | |

| Group variables | sex |

Variable type: numeric

| skim_variable | sex | n_missing | complete_rate | mean | sd | p0 | p25 | p50 | p75 | p100 | hist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rt | 0 | 0 | 1 | 243.23 | 49.85 | 158 | 214.25 | 236.0 | 268.75 | 414 | ▃▇▃▁▁ |

| rt | 1 | 0 | 1 | 264.84 | 37.45 | 222 | 237.00 | 251.5 | 283.25 | 362 | ▇▃▂▂▁ |

So sex==0 are running faster than the sex==1 and it would not be unreasonable to assume that sex==1 means women.

Race time is continuous and looks pretty normal. Yes the data are skewed by a single outlier (a race time of 414 minutes) but the mean and median are pretty similar (250 v. 242 minutes) and the 5th and 95th centile are very close to the values expected by adding or subtracting 1.64 times the SD from the mean (5th centile is 176, expected value using means and SD is 173; 95th centile actual and expected values are 328 and 328). I would probably feel comfortable reporting a mean and SD if you wanted.

Favorite running shoe: lesson2a %>% skim(shoe) gives a mean of 3.08 and a median of 3. If you reported these, you need therapy: shoe is a categorical variable and you should report the percentage of runners that favor each shoe.

AN ADDITIONAL IMPORTANT POINT: you should give the number of observations and the number of missing observations. n is 98 for all observations except for favorite running shoe, where there are 95 observations and 3 missing observations.

So here is a model answer, suitable for publication (assuming that sex==1 is coded as female).

| Characteristic | N = 981 |

|---|---|

| Age | 42 (10) |

| Women | 32 (33%) |

| Race time in minutes | 250 (47) |

| Favorite Running Shoe | |

| Asics | 14 (15%) |

| New Balance | 7 (7.4%) |

| Nike | 31 (33%) |

| Saucony | 43 (45%) |

| Unknown | 3 |

| 1 Mean (SD); n (%) | |

However, look at this.

| Characteristic | N = 981 |

|---|---|

| Age | 43 (34, 48) |

| Women | 32 (33%) |

| Race time in minutes | 242 (222, 274) |

| Favorite Running Shoe | |

| Asics | 14 (15%) |

| New Balance | 7 (7.4%) |

| Nike | 31 (33%) |

| Saucony | 43 (45%) |

| Unknown | 3 |

| 1 Median (Q1, Q3); n (%) | |

This really isn’t much to distinguish between these tables. On the one hand using the mean and SD gives you more information (e.g. what proportion of patients are aged over 70?). On the other hand, I can’t see anyone using a table 1 to do these types of calculation and the median and interquartile range give you some more immediately usable information (no multiplying by 1.64!).

9.2.2 lesson2b

Summarize average pain after the operation. Imagine you had to draw a graph of “time course of pain after surgery”. What numbers would you use for pain at time 1, time 2, time 3, etc.?

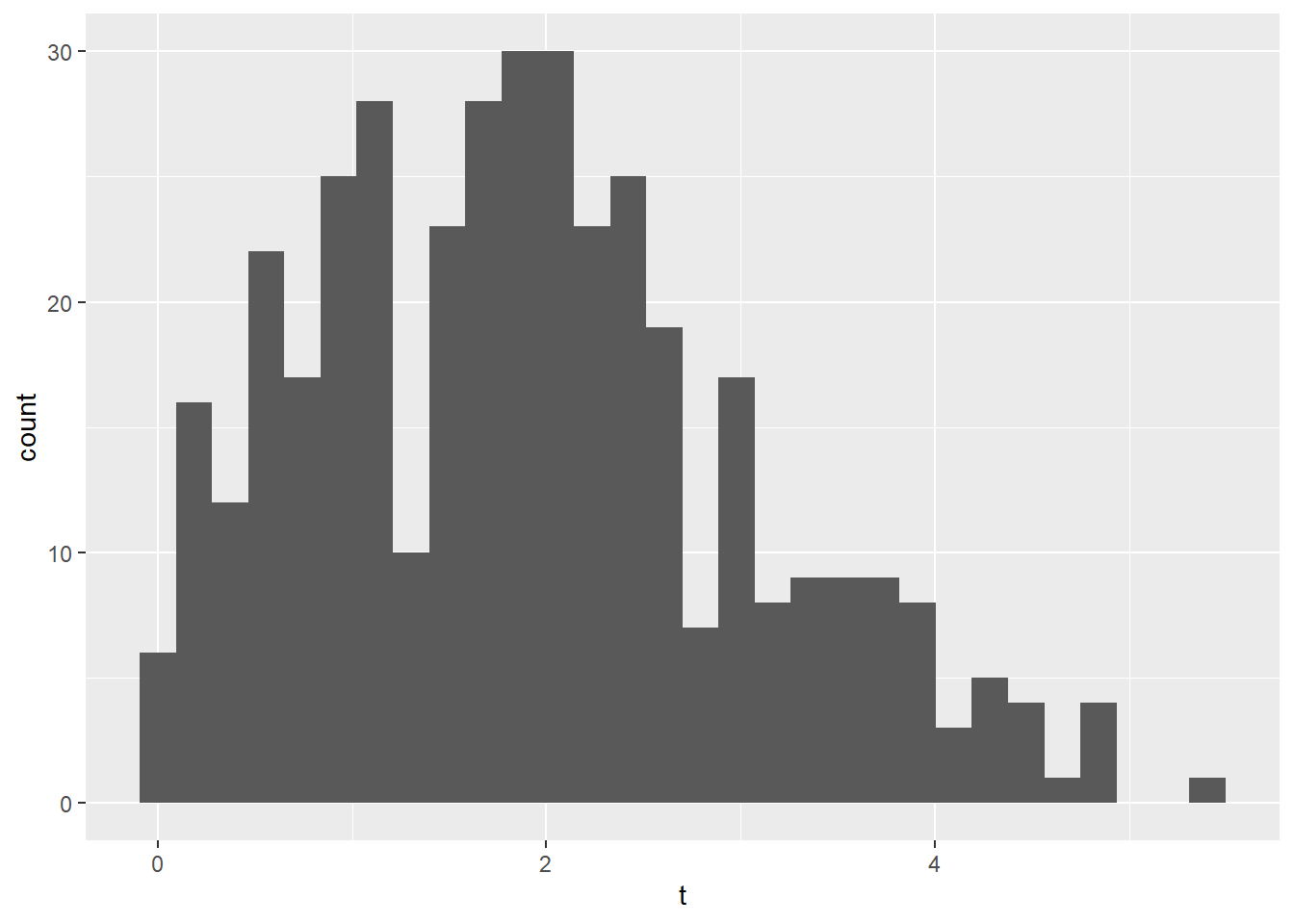

This is data on postoperative pain. You were asked to summarize average pain after the operation. This is continuous, so by looking at the histogram, you can see that the data look skewed. I would be tempted to use the median (1.8) and quartiles (1.1, 2.6).

# Create histogram to assess whether data look skewed

ggplot(data = lesson2b,

aes(x = t)) +

geom_histogram()## `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value `binwidth`.

However, using the mean and standard deviation doesn’t get you far off. For normal data, 50% of the observations are within two-thirds of a standard deviations of the mean. So the interquartile range predicted from the mean and SD would be 1.9 - 1.1*0.67 and 1.9 + 1.1*0.67 which gives you 1.2 and 2.7. This is an interesting point: the data can look skewed (and if you are interested, a statistical test can tell you that the data are definitely non-normal) but it doesn’t make much of a difference in practice.

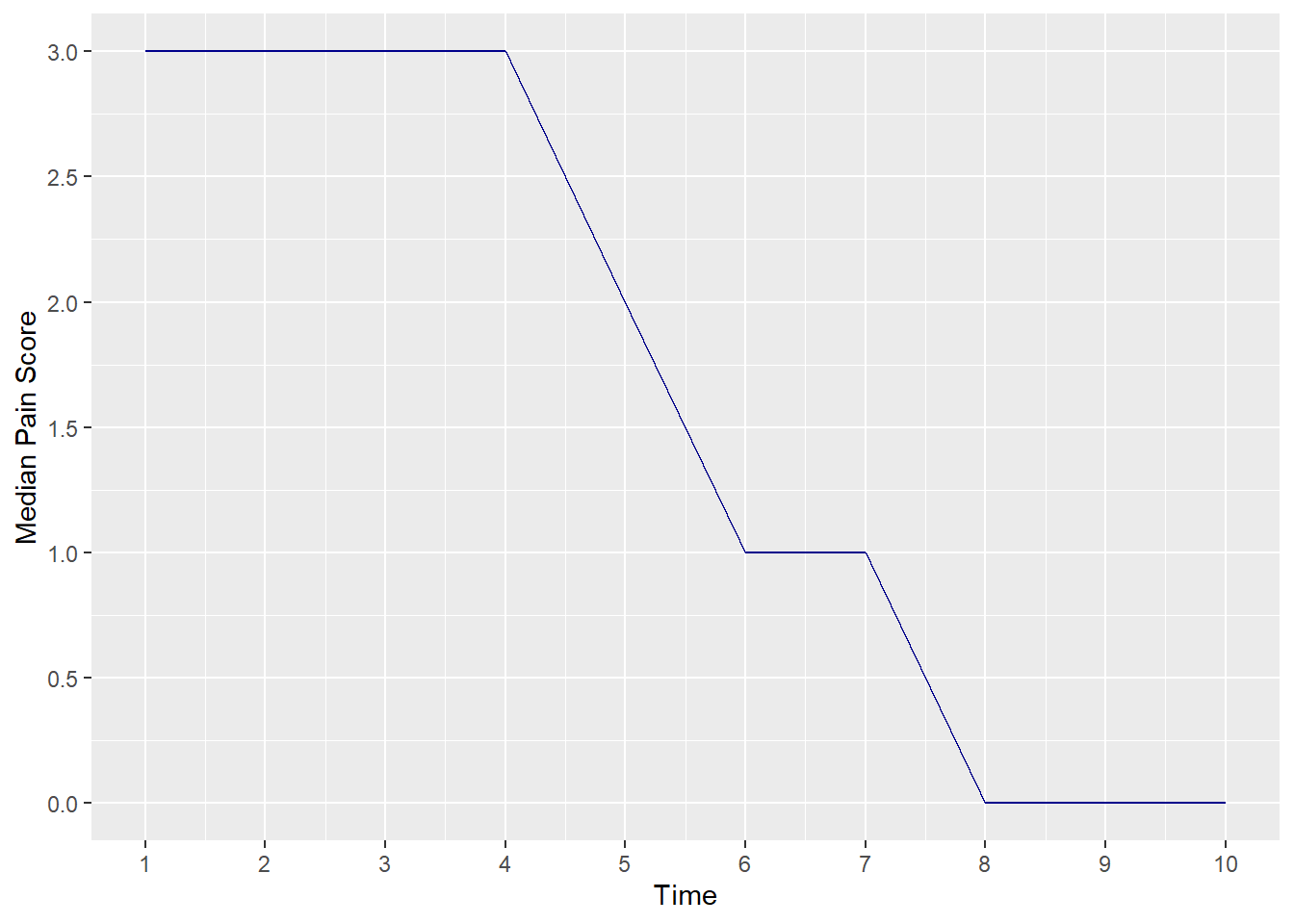

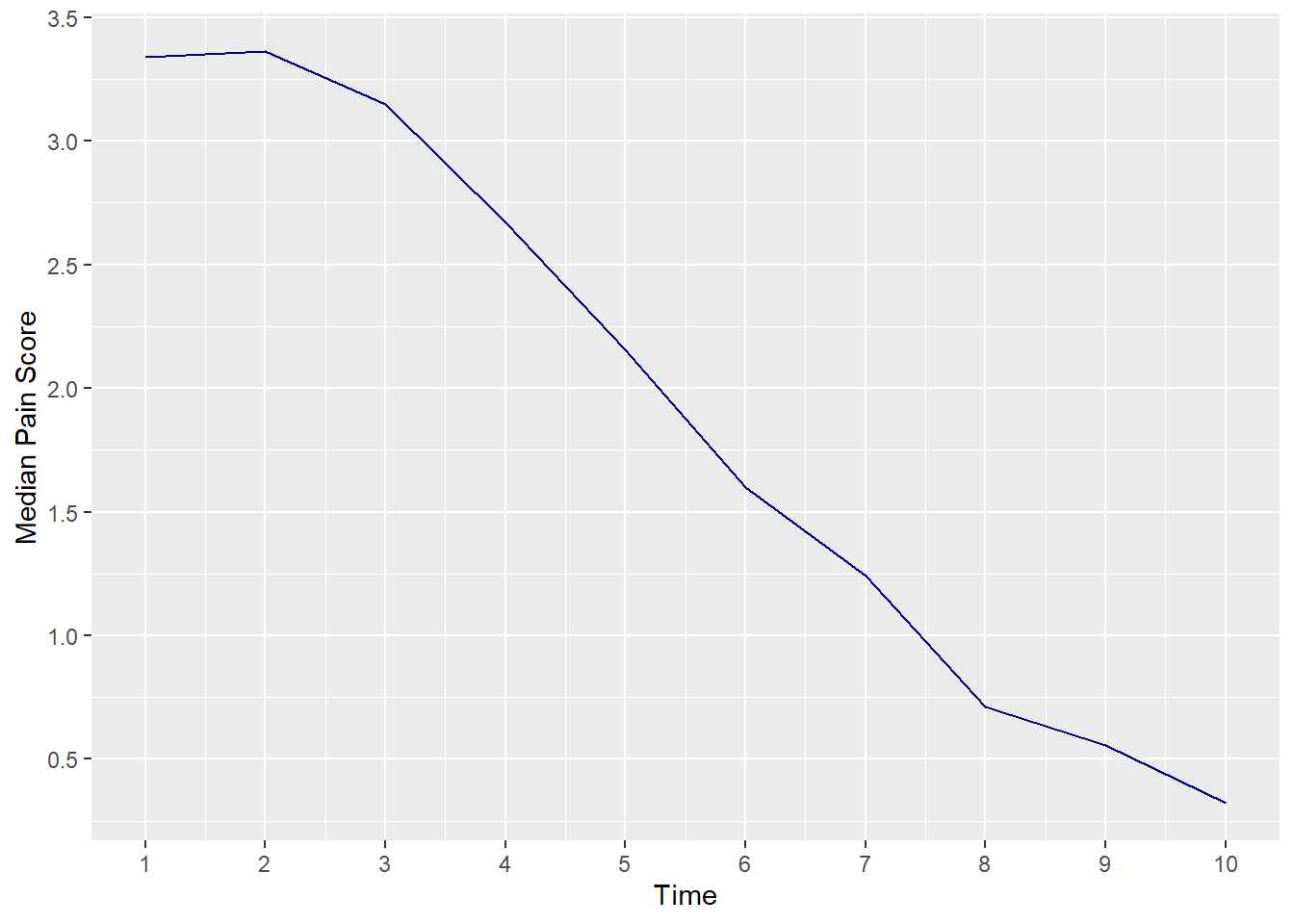

You were then asked to imagine that you had to draw a graph of “time course of pain after surgery”. What numbers would you use for time 1, time 2 etc? The first thing to note is that to draw the graph, which seems like a useful thing to do, you have to treat the data as continuous: you can’t really graph a table very easily. This is another illustration of how something that seems technically incorrect gives you useful approximations. Now that we have continuous data we have to decide whether to use medians or means. As it turns out, normality of the data isn’t even an issue. Here is what happens if you graph the median pain score at each time point.

This makes it seem that postoperative pain doesn’t change for four time points, then drops dramatically.

A graph using means seems more illustrative of what is really going on.

9.2.3 lesson2c

This is data on 241 patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. Summarize age, stage, grade and PSA.

One of the first things to look for here is missing data. If you type lesson2c %>% skim(), you’ll see that there is no missing data for age, 9 missing observations for PSA and 41 for grade. You will notice that the “stage” variable is not included here, because it is a character variable, not a numeric variable.

If you type tbl_summary(lesson2c %>% select(stage)), you’ll see that all patients have a stage assigned (no “NA” values).

A second issue is how to characterize the categorical variables. There are 8 different stages represented, many with very small numbers (like 2 for T4 and T1B, 4 for T3). It generally isn’t very helpful to slice and dice data into very small categories, so I would consider grouping. For instance, we could group the T1s together, and group the T3 and T4 patients together to get something like:

| Characteristic | N = 2411 |

|---|---|

| Stage | |

| T1 | 169 (70%) |

| T2A | 36 (15%) |

| T2B | 22 (9.1%) |

| T2C | 8 (3.3%) |

| T3/4 | 6 (2.5%) |

| 1 n (%) | |

To get this table, I created a new variable called “stage_category”.

The code below uses the case_when function, which is similar to the if_else function. Both functions take a condition and assign a value, but if_else can only assign two values (one if the condition is TRUE, the other if the condition is FALSE). case_when can assign as many values as you’d like.

In this case, the case_when function does the following:

- When the value of “stage” is one of the values in the list of “T1A”, “T1B”, or “T1C”, set the variable “stage_category” to “T1”.

- When the value of “stage” is “T3” or “T4”, set the variable “stage_category” to “T3/T4”.

- In

case_when, TRUE means “every observation that didn’t fall into any of the previous categories”. Here, this means: for all observations that didn’t fit into the previously specified “T1” or “T3/4” categories, use the value of the variable “stage”. In this case, these are the “T2A”, “T2B” and “T2C” values, which remain the same in both the “stage” and “stage_category” variables.

# Create new variable for stage and save into "lesson2c" dataset

lesson2c <-

lesson2c %>%

mutate(

stage_category =

case_when(

stage %in% c("T1A", "T1B", "T1C") ~ "T1",

stage %in% c("T3", "T4") ~ "T3/4",

TRUE ~ stage

)

)

# You can use the "count" function to confirm that your variable was created correctly

lesson2c %>% count(stage_category, stage)## # A tibble: 8 × 3

## stage_category stage n

## <chr> <chr> <int>

## 1 T1 T1A 3

## 2 T1 T1B 2

## 3 T1 T1C 164

## 4 T2A T2A 36

## 5 T2B T2B 22

## 6 T2C T2C 8

## 7 T3/4 T3 4

## 8 T3/4 T4 2There is a similar issue for grade, with few patients having grades 4, 5, 8 or 9. Now a key point is that what you decide to do in situations like this will often need to take into account your medical understanding. It might seems sensible to categorize grade as ≤6 or ≥7, or perhaps 4/5, 6, 7, 8/9. But as it turns out in prostate cancer, pathologists can’t reliably grade a cancer as 4 or 5 and these cancers should really be grouped with grade 6. Grade 8, on the other hand, signifies very aggressive disease and really needs to be reported separately even if there are only a few patients with grade 8. So grade would probably be summarized as per the following table:

| Characteristic | N = 2411 |

|---|---|

| Stage | |

| T1 | 169 (70%) |

| T2A | 36 (15%) |

| T2B | 22 (9.1%) |

| T2C | 8 (3.3%) |

| T3/4 | 6 (2.5%) |

| Grade | |

| 6 | 79 (40%) |

| 7 | 112 (56%) |

| 8 | 9 (4.5%) |

| Unknown | 41 |

| Age | 60 (56, 65) |

| PSA | 5.3 (4.0, 8.0) |

| Unknown | 9 |

| 1 n (%); Median (Q1, Q3) | |

9.2.4 lesson2d

Summarize cost.

I asked you to summarize the cost. You can see from a graph that the data are not normally distributed. If we were to follow the rule book slavishly, we would report a median and interquartile range. But what use is a median for cost data? We want to know “average” cost so that we can predict, for example, how much we should budget for next year. This requires a mean.

9.2.5 lesson2e

Summarize total cancer pain in one month in a group of chronic cancer patients.

The data are grossly non-normal and you could use the median pain score with interquartile range.

As for summarizing the number of days in pain, almost everyone has 31 days of pain. So I would give proportions of patients who had pain for 31 days and then the number who, say, had pain at least 3 out of every 4 days and 2 out of 4 days. There are two ways of doing this. You could use tbl_summary(lesson2e %>% select(f), type = list(f = "categorical")) and then combine some of the results. Or, and this is a little more complicated, you could create a new variable.

# Create variable to categorize number of days in pain

lesson2e <-

lesson2e %>%

mutate(

days =

case_when(

f <= 15 ~ 0,

f > 15 & f < 23 ~ 1,

f > 23 & f < 31 ~ 2,

f == 31 ~ 3

)

)In other words, create a new variable called “days”, and set it to 0 for anyone with 15 or less days of pain. Call anyone who has pain more than half the time (i.e. more than 15 days) a 1. Call anyone who has pain more than three quarter of the time (i.e. more than 23 days) a 2. Call anyone who has pain all the time a 3.

| Characteristic | N = 1001 |

|---|---|

| days | |

| 0 | 16 (17%) |

| 1 | 7 (7.4%) |

| 2 | 23 (24%) |

| 3 | 48 (51%) |

| Unknown | 6 |

| 1 n (%) | |

So you could report that, of the 94 patients with data on number of days with pain, 51% were in daily pain, 17% of patients had pain on less than half of days, 7.4% of patients had pain on more than half but less than 75% of days, 24% of patients had pain on more than 75% of days, but not every day.

For keen students only!

You could also try a log transformation of the pain scores. Create a new variable using log(pain).

Analyze this variable and you’ll see it appears normally distributed.

The mean of log is 5.42. You can transform the log back by calculating e5.42 (the function is exp(5.42)) to get 225, close to the median. Backtransforming the standard deviation is more complicated and can’t really be done directly. What you need to do is make any calculations you need on the log transformed scale and then backtransform the results. Imagine you wanted a 95% confidence interval. A 95% confidence interval is the mean ± 1.96 standard deviations. The standard deviation of the log data is close to one. So the confidence interval is 3.45 to 7.39. Transforming this exp(3.45) and exp(7.39) gives a confidence interval on the original scale of 31.44 and 1614.07. This is a reasonable approximation to the 5th (50) and 95th centile (1319).

9.3 Week 3

# Week 3: load packages

library(skimr)

library(gt)

library(gtsummary)

library(epiR)

library(broom)

library(pROC)

library(gmodels)

library(survival)

library(here)

library(tidyverse)

# Week 3: load data

lesson3a <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 3", "lesson3a.rds"))

lesson3b <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 3", "lesson3b.rds"))

lesson3c <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 3", "lesson3c.rds"))

lesson3d <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 3", "lesson3d.rds"))

lesson3e <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 3", "lesson3e.rds"))

lesson3f <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 3", "lesson3f.rds"))9.3.1 lesson3a

These are data from over 1000 patients undergoing chemotherapy reporting a nausea and vomiting score from 0 to 10. Does previous chemotherapy increase nausea scores? What about sex?

Hands up, who typed in t.test(nv ~ pc, data = lesson3a, var.equal = TRUE) without looking at the data? There are lots of missing data. There is a question as to whether you would actually analyze these data at all: could data be missing because patients were too ill to complete questionnaires? Could there have been bias in ascertaining who had prior chemotherapy? If you do decide to analyze, a t-test would be appropriate (t.test(nv ~ pc, data = lesson3a, var.equal = TRUE) and t.test(nv ~ sex, data = lesson3a, var.equal = TRUE)). A model answer might be:

Details of prior chemotherapy were available for 512 of the 1098 patients with nausea scores. Mean nausea scores were approximately 20% higher in the 255 patients with prior experience of chemotherapy (5.3; SD 2.03) than in the 257 chemotherapy-naive patients (4.5; SD 1.99). The difference between groups was small (0.8, 95% C.I. 0.5, 1.2) but highly statistically significant (p<0.001 by t-test), suggesting that prior chemotherapy increases nausea scores. Nausea scores were slightly lower in women (n=444; mean 4.7; SD 1.98) than men (n=434; mean 4.8; SD 2.1) but there were no statistically significant differences between the sexes (difference between means 0.1, 95% C.I. -0.2, 0.3; p=0.7 by t-test). However, far more women (131 / 575, 60%) than men (89 / 523, 40%) failed provide a nausea score (p=0.017 by chi squared), perhaps suggesting bias in reporting.

Now, I’ll explain what I did. First, I did the two t-tests:

# t-test for nausea/vomiting by prior chemotherapy

t.test(nv ~ pc, data = lesson3a, var.equal = TRUE)##

## Two Sample t-test

##

## data: nv by pc

## t = -4.6275, df = 510, p-value = 4.7e-06

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group 0 and group 1 is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -1.1699123 -0.4725841

## sample estimates:

## mean in group 0 mean in group 1

## 4.459144 5.280392##

## Two Sample t-test

##

## data: nv by sex

## t = 0.43835, df = 876, p-value = 0.6612

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group 0 and group 1 is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.2100764 0.3308988

## sample estimates:

## mean in group 0 mean in group 1

## 4.782258 4.721847While the t.test function gives the confidence interval around the difference in means, it does not calculate the difference in means for you. While you can cut and paste to calculate this manually, you can do it by using the tbl_summary and add_difference functions from the {gtsummary} package.

tbl_summary(

# Keep 2 variables of interest

lesson3a %>%

select(nv, pc),

by = pc,

# specify that you want mean (SD) rather than median (IQR)

statistic = list(nv = "{mean} ({sd})")

) %>%

# Use the "add_difference" function with the "ancova" test

add_difference(

test = list(nv = "ancova")

)| Characteristic | 0 N = 3211 |

1 N = 3181 |

Difference2 | 95% CI2 | p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nausea & vomiting grade 0 -10 | 4.46 (1.99) | 5.28 (2.03) | -0.82 | -1.2, -0.47 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 64 | 63 | |||

| 1 Mean (SD) | |||||

| 2 One-way ANOVA | |||||

| Abbreviation: CI = Confidence Interval | |||||

As you can see, the table above gives the same estimates as the t.test function. The table also gives additional information including the number of observations in each group, the number of missing observations in each group, and the difference in means between the two groups.

Next I created a new variable for missing data on nausea and vomiting:

# Create new variable to indicate whether "nv" variable is missing

lesson3a <-

lesson3a %>%

mutate(

missing =

if_else(is.na(nv), 1, 0)

)And then created a table to look at the missingness for this variable:

# Formatted table to look at rates of missingness in "nv" variable by sex

tbl_summary(

lesson3a %>% select(missing, sex),

by = sex,

type = list(missing = "categorical")

)| Characteristic | 0 N = 5231 |

1 N = 5751 |

|---|---|---|

| missing | ||

| 0 | 434 (83%) | 444 (77%) |

| 1 | 89 (17%) | 131 (23%) |

| 1 n (%) | ||

If you got that far: wow! (also, forget the course, you don’t need it). If you didn’t get that far, don’t feel bad about it, but try to get a handle on the thought process.

One other issue: the p-value for the first t-test (previous chemotherapy) is given as “p-value = 4.7e-06”. While this number is very close to 0, we cannot round to 0 - there is no such thing as a p-value of 0 for any hypothesis worth testing (there is a small but finite chance of every possible result, even throwing 100,000 tails in a row on an unbiased coin.) So do not report “p=0.0000”! You can round p-values for reporting - for example, “4.7e-06” can be rounded to “<0.0005”. As you can see, if you use the tbl_summary and add_difference functions from {gtsummary}, the p-value is automatically formatted in the table as “p<0.0001”.

For more advanced students:

The other thing you can do is to find out the precise p-value from the t value (which is given above the p-value: -4.6275). The function you need is pt(t value, degrees of freedom). This will give you the p-value for a one-sided test, so you must multiply by 2 to get the two-sided test p-value.

## [1] 4.699746e-06This p-value can also be read as 4.7 x 10-6. An interesting question though: is it important whether p is <0.0005 or 4.7 x 10-6?

What is “degrees of freedom” and how come it is 510? Think about it this way: You have a line of ten people outside your door. You know the mean age of this group. Each person comes in one-by-one, you try to guess their age and they tell you how old they actually are. As each person comes in, your guesses will get better and better (for example, if the first three people have ages less than the mean, you will guess the age of the fourth person as something above the mean). However, only when you have the ages of the first nine people will you be able to guess for sure the age of the next (and last) person. In other words, the ages of the first nine people are “free”, the age of the last person is “constrained”. So “degrees of freedom” is the sample size minus one. Little catch though: for an unpaired test (such a straight drug v. placebo trial), you have two different groups and two different means. You would therefore be able to predict the scores of two observations (the last patient in each group). Degrees of freedom in an unpaired test is therefore the total sample size minus two (or, put another way, the sample size in group a minus one plus the sample size in group b minus one).

9.3.2 lesson3b

Patients with wrist osteoarthritis are randomized to a new drug or placebo. Pain is measured before and after treatment. Is the drug effective?

The most obvious thing to do would be to do:

##

## Two Sample t-test

##

## data: p by g

## t = 1.9731, df = 34, p-value = 0.05665

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group 0 and group 1 is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.01930642 1.30819531

## sample estimates:

## mean in group 0 mean in group 1

## 0.55555555 -0.08888889This gives a p-value of 0.057 and you might conclude that although the difference wasn’t statistically significant, there was some evidence that the drug works. However, this t-test assumes that the data are independent. In the present case, this assumption does not hold: each patient contributes data from two wrists, and the pain scores from each wrist are correlated. There are several ways around the problem. The most obvious is to say: “These data are not independent, I am not going to analyze them. Call in a statistician.”

However, if you are really keen, you could try the following:

You could analyze the data from each wrist separately by creating new variables as shown below (lines with # are comments). Since the “before” and “after” measurements are coming from the same patient, we will need to use a paired t-test here.

# Analyze data separately by wrist

lesson3b <-

lesson3b %>%

# Create a new variable called "pright" equivalent to "p"

# (the pain score for the right wrist (site 2) only)

mutate(

pright = case_when(site == 2 ~ p)

# By default, any observations that do not fall into the specified conditions

# in the "case_when" statement will be set to missing (NA)

) %>%

# Create a new variable called "pleft" for pain scores for the left wrist

mutate(

pleft = case_when(site == 1 ~ p)

)

# t-test for pain in right and left wrists separately

t.test(pright ~ g, data = lesson3b, var.equal = TRUE)##

## Two Sample t-test

##

## data: pright by g

## t = 1.6818, df = 16, p-value = 0.112

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group 0 and group 1 is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.2055046 1.7832823

## sample estimates:

## mean in group 0 mean in group 1

## 0.6555555 -0.1333333##

## Two Sample t-test

##

## data: pleft by g

## t = 1.0418, df = 16, p-value = 0.313

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group 0 and group 1 is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.5174209 1.5174209

## sample estimates:

## mean in group 0 mean in group 1

## 0.45555555 -0.04444445You could also analyze the data by taking the average of the two wrists. You can create a new value for the average using the mean function. The distinct function from the {dplyr} package allows you to drop duplicate observations. Since there are two observations per patient (one for the left wrist and one for the right wrist), we will take the average and then drop the duplicate observation so that each patient is included only once.

lesson3b_avg <-

lesson3b %>%

# Grouping by "id" so that each patient ends up with the average of their own two wrist scores

group_by(id) %>%

# Calculate the mean pain score between wrists for each patient

mutate(

meanpain = mean(p, na.rm = TRUE)

) %>%

# Only keep the patient ID, group variable and mean pain score

select(id, g, meanpain) %>%

# Drop duplicates so you don't count each patient twice

# Here we only want one observation per patient since we are assessing the average pain between the two wrists

distinct() %>%

# Ungroup the data

ungroup()

# t-test for average pain between both wrists

t.test(meanpain ~ g, data = lesson3b_avg, var.equal = TRUE)##

## Two Sample t-test

##

## data: meanpain by g

## t = 1.4286, df = 16, p-value = 0.1723

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group 0 and group 1 is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.3118365 1.6007254

## sample estimates:

## mean in group 0 mean in group 1

## 0.55555555 -0.088888899.3.3 lesson3c

Some postoperative pain data again. Is pain on day 2 different than pain on day 1? Is pain on day 3 different from pain on day 2?

The most obvious issue here is that you are measuring the same patients on two occasions, so you are going to want a paired test. Should you do a paired t-test? Many statisticians would prefer a non-parametric method given that the data take only five different values and that the number of observations is small. The following command gives you the “Wilcoxon signed rank test”:

# Non-parametric test comparing day 1 and day 2 pain

wilcox.test(lesson3c$t1, lesson3c$t2, paired = TRUE)## Warning in wilcox.test.default(lesson3c$t1, lesson3c$t2, paired = TRUE): cannot

## compute exact p-value with ties## Warning in wilcox.test.default(lesson3c$t1, lesson3c$t2, paired = TRUE): cannot

## compute exact p-value with zeroes##

## Wilcoxon signed rank test with continuity correction

##

## data: lesson3c$t1 and lesson3c$t2

## V = 41.5, p-value = 0.1446

## alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0If you run this code, you will notice you get a warning in yellow text that states that the “exact p-value” cannot be calculated. In R, “warnings” are notes that indicate you may want to look more closely at your code, but won’t stop the code from running - as you can see, this code still gives a p-value - but R is also flagging this result to tell you that this is not an “exact” p-value (you will learn more about exact p-values later). You should always take note of warnings when they occur, but sometimes you may not need to make any changes to the code.

(By the way: I know this because that is what it says on the read out. If you had asked me yesterday, I doubt I would have remembered the name of a non-parametric paired test, another reason to think in concepts rather than remembering statistical techniques). The p-value you get is p=0.14. We cannot conclude that pain scores are different. But is that all we want to say? The number of patients is small, maybe we failed to spot a difference. So let’s try a t-test:

# paired t-test comparing day 1 and day 2 pain

t.test(lesson3c$t1, lesson3c$t2, paired = TRUE, var.equal = TRUE)##

## Paired t-test

##

## data: lesson3c$t1 and lesson3c$t2

## t = 1.5467, df = 21, p-value = 0.1369

## alternative hypothesis: true mean difference is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.09395838 0.63941292

## sample estimates:

## mean difference

## 0.2727273The p-value you get (p=0.14) is very similar to the non-parametric method and you get a confidence interval for the difference between means of -0.09, 0.64. What I would conclude from this is that pain is unlikely to be worse on day 2 than day 1 but any decrease in pain is probably not important.

What about normality of the data? Doesn’t that figure into whether you assess by t-test or non-parametric? Well if you type look at the distribution of t1 and t2, you find that neither are normally distributed. But a paired t-test does not depend on the assumption that each set of data in a pair is distributed but that the differences between pairs are normally distributed. So you would have to create a new variable and look at that:

# Create a variable containing the difference in pain scores between days 1 and 2

lesson3c <-

lesson3c %>%

mutate(delta12 = t2 - t1)

# Summarize change in pain scores

skim(lesson3c$delta12)| Name | lesson3c$delta12 |

| Number of rows | 22 |

| Number of columns | 1 |

| _______________________ | |

| Column type frequency: | |

| numeric | 1 |

| ________________________ | |

| Group variables | None |

Variable type: numeric

| skim_variable | n_missing | complete_rate | mean | sd | p0 | p25 | p50 | p75 | p100 | hist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| data | 0 | 1 | -0.27 | 0.83 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ▁▃▁▇▂ |

As it turns out, the distribution of differences between pain scores are normally distributed even though pain at time 2 does not have a normal distribution. In fact, this is almost always the case.

Now let’s compare t2 and t3.

##

## Paired t-test

##

## data: lesson3c$t2 and lesson3c$t3

## t = 1.2501, df = 21, p-value = 0.225

## alternative hypothesis: true mean difference is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.2412859 0.9685587

## sample estimates:

## mean difference

## 0.3636364Again, no significant difference. Does this mean that pain does not decrease after an operation? Of course, we know that pain does indeed get better. This illustrates two points: first, don’t ask questions you know the answer to; second, asking lots of questions (is pain on day 2 better than on day 1?; is pain on day 3 better on day 2?) is not as good as just asking one question: does pain decrease over time? We’ll discuss how to answer this question later on in the course.

9.3.4 lesson3d

This is a single-arm, uncontrolled study of acupuncture for patients with neck pain. Does acupuncture increase range of motion? Just as many men as women get neck pain. Can we say anything about the sample chosen for this trial with respect to gender? The mean age of patients with neck pain is 58.2 years. Is the trial population representative with respect to age?

This is before and after data, so again you’ll want a paired test. The data are continuous, so a paired t-test is an option (if you are worried about normality, do both the parametric and non-parametric test and compare the results.)

There are two ways of doing the t-test:

- Test whether the baseline scores are different from the post-treatment scores:

# paired t-test for before and after pain scores

t.test(lesson3d$b, lesson3d$a, paired = TRUE, var.equal = TRUE)##

## Paired t-test

##

## data: lesson3d$b and lesson3d$a

## t = -4.4912, df = 33, p-value = 8.19e-05

## alternative hypothesis: true mean difference is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -35.17110 -13.24067

## sample estimates:

## mean difference

## -24.20588- Test whether the difference between scores is different from zero:

# t-test for whether difference between before and after scores is different than zero

t.test(lesson3d$d, mu = 0)##

## One Sample t-test

##

## data: lesson3d$d

## t = 4.4912, df = 33, p-value = 8.19e-05

## alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 13.24067 35.17110

## sample estimates:

## mean of x

## 24.20588Both methods give you an identical p-value of <0.001. But note, I didn’t ask for the p-value. I asked “Does acupuncture increase range of motion?” Given that this is an uncontrolled trial, it may be that range of motion has improved naturally over time. So in fact you can’t answer the question about whether acupuncture increases range of motion from these data!

BTW: for those who are interested, acupuncture has been shown to improve neck pain and range of motion in a controlled trial, see: Irnich, Behrens et al., Immediate effects of dry needling and acupuncture at distant points in chronic neck pain: results of a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled crossover trial.

# Test whether proportion of women is different from 50%

binom.test(sum(lesson3d$sex), nrow(lesson3d %>% filter(!is.na(sex))), p = 0.5)##

## Exact binomial test

##

## data: sum(lesson3d$sex) and nrow(lesson3d %>% filter(!is.na(sex)))

## number of successes = 9, number of trials = 34, p-value = 0.009041

## alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is not equal to 0.5

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.1288174 0.4436154

## sample estimates:

## probability of success

## 0.2647059Only about a quarter of the patients are women, and the binomial test gives a p-value of 0.009, suggesting that men are over-represented in this trial. But is this important?

##

## One Sample t-test

##

## data: lesson3d$age

## t = -2.261, df = 33, p-value = 0.03048

## alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 58.2

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 46.30921 57.57315

## sample estimates:

## mean of x

## 51.94118Similarly, this t-test for age gives a p-value of 0.030, but I doubt anyone would call a mean age of 52 much different from a mean age of 58, so you’d probably want to say that, ok, the trial patients are younger than we might expect, but not by much.

9.3.5 lesson3e

These data are length of stay from two different hospitals. One of the hospitals uses a new chemotherapy regime that is said to reduce adverse events and therefore length of stay. Does the new regime decrease length of stay?

Well, before running off and doing t-tests, let’s have a look at the data:

| Name | Piped data |

| Number of rows | 57 |

| Number of columns | 2 |

| _______________________ | |

| Column type frequency: | |

| numeric | 1 |

| ________________________ | |

| Group variables | hospital |

Variable type: numeric

| skim_variable | hospital | n_missing | complete_rate | mean | sd | p0 | p25 | p50 | p75 | p100 | hist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| los | a | 0 | 1 | 44.86 | 13.57 | 30 | 34.00 | 41 | 55.0 | 79 | ▇▇▃▂▂ |

| los | b | 0 | 1 | 45.14 | 10.85 | 28 | 39.25 | 45 | 50.5 | 70 | ▃▇▇▃▂ |

This shows us the mean, median, etc. for length of stay by hospital. The two sets of data look very similar. Regardless of whether we do a t-test or non-parametric test, we do not see a difference between groups, p is >0.9 or 0.7. Interesting question: should you report a 95% confidence interval for the difference between groups? This shows, for example, that the new regimen could reduce length of stay by up to six days, surely important in cost terms. On the other hand, this is not a randomized trial. There might be all sorts of differences between the hospitals other than the different chemotherapy regime, such as the mix of patients, discharge policies etc. So you would have to be careful in stating that the chemotherapy regime “could reduce hospital stay by as much as six days” or some such.

For advanced students only:

The data are non-normally distributed so you could try a log transform:

The distribution of this new variable for both groups combined is normal, therefore data in each group will be normal. Try a t-test:

# paired t-test using log of length of stay as outcome

t.test(loglos ~ hospital, data = lesson3e, var.equal = TRUE)##

## Two Sample t-test

##

## data: loglos by hospital

## t = -0.29426, df = 55, p-value = 0.7697

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group a and group b is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.1594693 0.1186343

## sample estimates:

## mean in group a mean in group b

## 3.762733 3.783150The p-value is similar to the untransformed analyses. Now, look at the difference between means -0.02 and 95% confidence interval (-0.16, 0.12).

To backtransform these values, you have to remember that addition on a log scale is the same as multiplication on an untransformed scale. Backtransform -0.02 using exp(-0.02) and you get 0.98. In other words, length of stay in hospital a is 98% more (or 2.0% less) compared to hospital b. Do the same things with the upper and lower bounds of the confidence interval and you might conclude that the difference in length of stay is between 15% less in hospital a to 13% less in hospital b. If you wanted to convert these numbers to actual days, just multiply by the mean hospital stay in group b by 0.98, 0.85 and 1.13.

9.3.6 lesson3f

These data are from a randomized trial on the effects of physiotherapy treatment on function in pediatric patients recovering from cancer surgery. Function is measured on a 100 point scale. Does physiotherapy help improve function?

You will want to do an unpaired t-test or non-parametric test on these data.

# unpaired t-test for change in pain by physiotherapy group

t.test(delta ~ physio, data = lesson3f, var.equal = TRUE)##

## Two Sample t-test

##

## data: delta by physio

## t = -1.4868, df = 110, p-value = 0.1399

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group 0 and group 1 is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -16.668572 2.378662

## sample estimates:

## mean in group 0 mean in group 1

## 11.70690 18.85185This gives a p-value of 0.14 (incidentally, don’t say “p > 0.05” or “p=0.1399”, which are under- and over-precise, respectively). Given a p-value greater than 5%, we would say that we found no evidence that the treatment was effective. But is this really the case? Look at the read out from the t-test again, particularly the means for each group and the difference. The improvements in the treatment group was about 50% greater than in controls. The 95% confidence interval for the difference includes a possible 17 point improvement on physiotherapy, more than twice that of controls. So physiotherapy might well be a clinically important treatment in this population, even if we failed to prove it was better than control in this trial. Whatever your conclusion, don’t just report the p-value: report the means and standard deviations in each group separately plus the difference between means and a 95% confidence interval. If I was writing this up for a journal, I might say:

Mean improvement in function was greater in the 54 physiotherapy group patients (18.9 points, SD 24.6) than in the 58 controls (11.7, SD 26.1). Although by t-test the difference between groups (7.1) was not statistically significant (p=0.14), the 95% confidence interval (-2.4, 17) includes clinically relevant effects. This suggests that the trial may have been underpowered to detect meaningful differences between groups.

An alternative conclusion, which I think I actually prefer, would be to focus on the difference between groups of 7.1, deciding whether this is clinically significant.

9.4 Week 4

# Week 4: load packages

library(skimr)

library(gt)

library(gtsummary)

library(epiR)

library(broom)

library(pROC)

library(gmodels)

library(survival)

library(here)

library(tidyverse)

# Week 4: load data

lesson4a <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 4", "lesson4a.rds"))

lesson4b <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 4", "lesson4b.rds"))

lesson4c <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 4", "lesson4c.rds"))

lesson4d <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 4", "lesson4d.rds"))

lesson4e <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 4", "lesson4e.rds"))9.4.1 lesson4a

This is a dataset on fifteen patients recording whether they had problematic nausea or vomiting after chemotherapy (defined as grade 2 or higher for either nausea or vomiting) and whether they reported being prone to travel sickness. Does travel sickness predict chemotherapy nausea and vomiting?

To have a quick look at the data, create a two-by-two table:

# Create formatted table of nausea/vomiting by car sickness history

tbl_summary(

lesson4a %>% select(nv, cs),

by = cs,

type = list(nv = "categorical")

)| Characteristic | 0 N = 61 |

1 N = 91 |

|---|---|---|

| grade 2 or above nausea 1 =yes | ||

| 0 | 4 (67%) | 4 (44%) |

| 1 | 2 (33%) | 5 (56%) |

| 1 n (%) | ||

This shows, for example, 56% of those who get car sick reported problematic nausea compared to only 33% of those who aren’t prone to car sickness. To find out whether this is statistically significant (it certainly seems clinically significant), you can use the chisq.test or the fisher.test function. For the chisq.test function, remember to use the correct = FALSE option to get the p-value without continuity correction.

##

## Pearson's Chi-squared test

##

## data: table(lesson4a$nv, lesson4a$cs)

## X-squared = 0.71429, df = 1, p-value = 0.398##

## Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data

##

## data: table(lesson4a$nv, lesson4a$cs)

## p-value = 0.6084

## alternative hypothesis: true odds ratio is not equal to 1

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.1989474 39.4980687

## sample estimates:

## odds ratio

## 2.348722chisq.test gives the p-value from a chi-squared test, fisher.test is a special form of this test when any of the numbers in the table are small, say 10 or below in any cell. The p-value is about 0.6. You now have 3 options:

- Declare the result non-statistically significant, and conclude that you have failed to reject the null hypothesis of no difference between groups.

- Say that, though differences between groups were not statistically significant, sample size was too small.

- Say that differences between groups were not statistically significant, and that the study was too small, but try to quantify a plausible range of possible differences between groups.

For point 3, you need the confidence interval. You get this by using the epi.2by2 command. Remember that if you want to compare the “exposed” to the “non-exposed” group, you will need to use the factor function and reverse the sort order for the two variables.

# Confidence interval for difference between groups

epi.2by2(

table(

factor(lesson4a$cs, levels = c(1, 0)),

factor(lesson4a$nv, levels = c(1, 0))

)

)## Outcome+ Outcome- Total Inc risk *

## Exposure+ 5 4 9 55.56 (21.20 to 86.30)

## Exposure- 2 4 6 33.33 (4.33 to 77.72)

## Total 7 8 15 46.67 (21.27 to 73.41)

##

## Point estimates and 95% CIs:

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Inc risk ratio 1.67 (0.47, 5.96)

## Inc odds ratio 2.50 (0.29, 21.40)

## Attrib risk in the exposed * 22.22 (-27.54, 71.99)

## Attrib fraction in the exposed (%) 40.00 (-82.13, 84.02)

## Attrib risk in the population * 13.33 (-32.06, 58.72)

## Attrib fraction in the population (%) 28.57 (-5.87, 79.65)

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Yates corrected chi2 test that OR = 1: chi2(1) = 0.100 Pr>chi2 = 0.751

## Fisher exact test that OR = 1: Pr>chi2 = 0.608

## Wald confidence limits

## CI: confidence interval

## * Outcomes per 100 population unitsThis gives a “risk ratio” (same as relative risk) of 1.67 with a 95% CI 0.47, 5.96. A model answer might be:

Five of the nine patients (NA%) who reported prior car sickness had grade 2 or higher nausea and vomiting compared to two of the six (NA%) who reported no prior car sickness. Though differences between groups were not statistically significant (p=0.6 by Fisher’s exact test), the sample size was small and the 95% confidence interval for the difference between groups includes differences of clinical relevance (relative risk 1.67; 95% CI 0.47, 5.96). It may be, for example, that problematic nausea and vomiting is up to six times more common in patients reporting prior car sickness than in those who do not.

9.4.2 lesson4b

An epidemiological study of meat consumption and hypertension. Meat consumption was defined as low, medium or high depending on whether subjects ate less than 3, 3 to 7 or 7 + meals with meat per week. Does meat consumption lead to hypertension?

There are three levels of meat consumption. The outcome (hypertension) is binary, either 1 or 0. So we will have a 3 by 2 table. Let’s start with a quick look:

# Formatted table of meat consumption by hypertension status

tbl_summary(

lesson4b %>% select(meat, hbp),

by = hbp

)| Characteristic | 0 N = 351 |

1 N = 711 |

|---|---|---|

| consumption 1=lo, 2=med, 3=hi | ||

| 1 | 16 (46%) | 16 (23%) |

| 2 | 10 (29%) | 13 (18%) |

| 3 | 9 (26%) | 42 (59%) |

| 1 n (%) | ||

This would tell you, for example, that of the patients with hypertension, 59% ate a lot of meat and only 23% ate a little. I find this a less helpful statistic than presenting the data in terms of rates of hypertension for level of meat consumption. One other thing to notice is that the rates of hypertension are high, suggesting this is a selected population.

You also could have created this table:

# Formatted table of meat consumption by hypertension status (row percents)

tbl_summary(

lesson4b %>% select(meat, hbp),

by = hbp,

percent = "row"

)| Characteristic | 0 N = 351 |

1 N = 711 |

|---|---|---|

| consumption 1=lo, 2=med, 3=hi | ||

| 1 | 16 (50%) | 16 (50%) |

| 2 | 10 (43%) | 13 (57%) |

| 3 | 9 (18%) | 42 (82%) |

| 1 n (%) | ||

These tables show the number and percentages of patients with hypertension in each category of meat eating. Rates of hypertension are 50%, 57% and 82% in the low, medium and high meat consumption groups, respectively.

To assess statistical significance, use the chisq.test function with the hypertension by meat consumption table as the input.

# Chi squared test for association between meat consumption and hypertension

chisq.test(table(lesson4b$hbp, lesson4b$meat), correct = FALSE)##

## Pearson's Chi-squared test

##

## data: table(lesson4b$hbp, lesson4b$meat)

## X-squared = 10.759, df = 2, p-value = 0.004611The p-value is p=0.005. How to interpret this? The formal statistical interpretation is that we can reject the null hypothesis that rates of hypertension are the same in each group. To demonstrate this, try renumbering the labels for the variable meat:

# Change values of meat consumption variable

lesson4b_changed <-

lesson4b %>%

mutate(

meat =

case_when(

meat == 3 ~ 0.98573,

meat == 2 ~ 60,

meat == 1 ~ 643

)

)

# Re-run chi squared test

chisq.test(table(lesson4b_changed$hbp, lesson4b_changed$meat), correct = FALSE)##

## Pearson's Chi-squared test

##

## data: table(lesson4b_changed$hbp, lesson4b_changed$meat)

## X-squared = 10.759, df = 2, p-value = 0.004611You get exactly the same result. This demonstrates that: a) the numbers you use for meat consumption act only as labels; b) the order is unimportant: you get the same p-value if you arrange the columns “low med hi” as “hi low med”.

So it might be useful to do what are called “pairwise” comparisons: what difference is there in the rate of hypertension between low and medium meat eaters? What about high and low? Though there are three possible comparisons (hi v. lo; hi v. med; med v. lo), it is more usual to chose either the highest or lowest category and compare everything to that. The way to do these analyses is to create new variables. The code is given below (the #s are comments that are ignored by R).

# Create a new variable "c1" which is "1" if meat consumption is high and "0" if it is medium

# "c1" is missing for low meat consumption: these patients are left out of the analysis

lesson4b <-

lesson4b %>%

mutate(

c1 =

case_when(

meat == 2 ~ 0,

meat == 3 ~ 1

)

)

# Test for difference between medium and high meat consumption

epi.2by2(

table(

factor(lesson4b$c1, levels = c(1, 0)),

factor(lesson4b$hbp, levels = c(1, 0))

)

)## Outcome+ Outcome- Total Inc risk *

## Exposure+ 42 9 51 82.35 (69.13 to 91.60)

## Exposure- 13 10 23 56.52 (34.49 to 76.81)

## Total 55 19 74 74.32 (62.84 to 83.78)

##

## Point estimates and 95% CIs:

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Inc risk ratio 1.46 (1.00, 2.13)

## Inc odds ratio 3.59 (1.20, 10.73)

## Attrib risk in the exposed * 25.83 (3.03, 48.63)

## Attrib fraction in the exposed (%) 31.37 (5.41, 55.94)

## Attrib risk in the population * 17.80 (-4.77, 40.37)

## Attrib fraction in the population (%) 23.95 (8.32, 45.11)

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Uncorrected chi2 test that OR = 1: chi2(1) = 5.542 Pr>chi2 = 0.019

## Fisher exact test that OR = 1: Pr>chi2 = 0.024

## Wald confidence limits

## CI: confidence interval

## * Outcomes per 100 population units# Compare high vs low consumption

# "c2" is "1" if meat consumption is high and "0" if it is low

# "c2" is missing for medium meat consumption: these patients are left out of the analysis

lesson4b <-

lesson4b %>%

mutate(

c2 =

case_when(

meat == 1 ~ 0,

meat == 3 ~ 1

)

)

# Test for difference between low and high meat consumption

epi.2by2(

table(

factor(lesson4b$c2, levels = c(1, 0)),

factor(lesson4b$hbp, levels = c(1, 0))

)

)## Outcome+ Outcome- Total Inc risk *

## Exposure+ 42 9 51 82.35 (69.13 to 91.60)

## Exposure- 16 16 32 50.00 (31.89 to 68.11)

## Total 58 25 83 69.88 (58.82 to 79.47)

##

## Point estimates and 95% CIs:

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Inc risk ratio 1.65 (1.14, 2.38)

## Inc odds ratio 4.67 (1.72, 12.68)

## Attrib risk in the exposed * 32.35 (12.11, 52.59)

## Attrib fraction in the exposed (%) 39.29 (15.88, 59.80)

## Attrib risk in the population * 19.88 (-0.06, 39.82)

## Attrib fraction in the population (%) 28.45 (14.29, 45.79)

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Uncorrected chi2 test that OR = 1: chi2(1) = 9.778 Pr>chi2 = 0.002

## Fisher exact test that OR = 1: Pr>chi2 = 0.003

## Wald confidence limits

## CI: confidence interval

## * Outcomes per 100 population unitsWhat these commands do is to create new variables (c1 and c2) that are used instead of the variable “meat” in analyses. These are set to 1 or 0 or missing depending on the pairwise comparison that you want to do. A model answer might be as follows:

The results of the study are shown in the table. Differences in rates of hypertension between categories of meat consumption are statistically significant (p=0.005). Rates of hypertension rise with increasing meat consumption: patients with the highest meat consumption had a risk of hypertension 1.5 times greater than those with intermediate meat consumption (95% CI 1.0, 2.1, p=0.019) and 1.6 times greater than those with the lowest levels of meat consumption (95% CI 1.1, 2.4, p=0.002). Rates of hypertension were similar between medium and low meat consumption (relative risk 1.1; 95% CI 0.69, 1.9, p=0.6).

| Characteristic | No Hypertension N = 351 |

Hypertension N = 711 |

Overall N = 1061 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meat Consumption | |||

| Low | 16 (50%) | 16 (50%) | 32 (100%) |

| Medium | 10 (43%) | 13 (57%) | 23 (100%) |

| High | 9 (18%) | 42 (82%) | 51 (100%) |

| 1 n (%) | |||

You might note that I chose to compare low and medium meat consumption, that is, give all three pairwise comparisons rather than just high v. low and high v. medium. This is probably the exception rather than the rule: in this particular case, it seems worth reporting because the low and medium groups seem very comparable compared to high meat consumption.

And now, the key point…

You may have noticed that my model answer did not actually answer the question. The question was “does meat consumption lead to hypertension?”. I only answered in terms of rates of hypertension rising with increased meat consumption and the like. This is because you cannot use statistics to prove causality without thinking about the research design. If you go out and ask how much meat people eat and then measure their blood pressure, you cannot assume that any associations are causal. It may be, for example, that meat eaters tend to smoke more and it is smoking, not meat, that causes hypertension.

9.4.3 lesson4c

This is a dataset from a chemotherapy study. The researchers think that a mutation of a certain gene may be associated with chemotherapy toxicity. Should clinicians test for the gene during pre-chemotherapy work up?

It is immediately obvious from this table that there are very few patients who are homozygous mutant type.

# Formatted two-way table of genes by toxicity outcome

tbl_summary(

lesson4c %>% select(gene, toxicity),

by = toxicity

)| Characteristic | 0 N = 2041 |

1 N = 1001 |

|---|---|---|

| 0=homozygous wild type; 1=heterozygous; 2 = homozygous mutant | ||

| 0 | 134 (66%) | 80 (80%) |

| 1 | 65 (32%) | 19 (19%) |

| 2 | 5 (2.5%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| 1 n (%) | ||

It would seem appropriate to combine heterozygotes and homozygous mutant type into a single category. You might be tempted to type lesson4c %>% mutate(gene = if_else(gene == 2, 1, gene)). But you should avoid changing raw data in this way: it would be preferable to create a new variable as follows:

# Create binary variable grouping the values of "1" and "2" for gene

lesson4c <-

lesson4c %>%

mutate(

mutant =

case_when(

gene == 1 | gene == 2 ~ 1,

gene == 0 ~ 0

)

)Moreover, it would be worth reporting the results of an analysis using all three groups, to investigate whether the conclusions change. This is sometimes called a “sensitivity analysis”.

The results of the study are shown in the table. Very few participants (6 (2.0%)) were homozygous mutant. For the purposes of analysis therefore, data for these participants was combined with those heterozygous for the gene. Patients with any mutant allele (i.e. heterozygous or homozygous mutant) had lower rates of toxicity (20% vs 80%, p=0.010 by chi squared). The relative risk of toxicity is 0.59 compared to patients with the wild-type (95% CI 0.39, 0.91). This conclusion is not sensitive to the method of analysis: analysis of the table keeping participants in three groups gives p=0.033 by an exact test. These findings should be confirmed in a larger series. In particular, it would be interesting to know whether patients who are homozygous mutant are at particularly increased risk.

| Characteristic | No Grade III/IV Toxicity N = 2041 |

Grade III/IV Toxicity N = 1001 |

Overall N = 3041 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | |||

| Homozygous wild type | 134 (63%) | 80 (37%) | 214 (100%) |

| Heterozygous | 65 (77%) | 19 (23%) | 84 (100%) |

| Homozygous mutant | 5 (83%) | 1 (17%) | 6 (100%) |

| 1 n (%) | |||

Genetics type people: note that this gene is in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium!

One thing to note is my conclusion, the answer to the question. It would be a little premature to start changing clinical practice on the basis of a single study with a moderate number of patients and a less than overwhelming strength of evidence. Also, it is questionable whether you should start using a test just because it is predictive: you should use a test if it improves clinical outcome.

9.4.4 lesson4d

Patients are given chemotherapy regimen a or b and assessed for tumor response. Which regimen would you recommend to a patient? Do the treatments work differently depending on age or sex?

The first thing we want to do is compare response by group. But using epi.2by2 with “response” and “chemo” doesn’t work. This is because the exposure variable has to be numeric (for example, 0 and 1), not “a” or “b”. So you need to use the “group” variable instead of the “chemo” variable.

This gives response rates of 49% on regimen “a” and 41% on regimen “b”, a relative risk of 0.84 and a p-value of 0.11. Should we conclude that there is no difference between groups and that you should feel free to use either regimen? Imagine you are a patient. You are told that you have a 50:50 chance of response on one regimen but only a 40% chance on the other. Unless there are good reasons to choose between the regimes (e.g. toxicity), which would you choose? The point here is that statistical significance does not really inform choices between similar alternatives. Assuming that toxicity, cost and inconvenience are similar between the regimes, I would recommend regimen a, even though the difference is not statistically significant. The confidence interval here is absolutely critical: the 95% C.I. for the risk difference is 0.67%, 1.0%. In other words, the response rate could be 0.67% higher on regimen a (e.g. 55% vs. 56%) or 2% lower (e.g. 50% vs. 51%). So you might do a lot better with regimen a, you are unlikely to do much worse.

The sub-group analyses

A common mistake would be to use epi.2by2 with “response” and “sex”. However, this would examine whether, regardless of chemotherapy regimen used, men and women had different tumor outcome. What we want to see if the difference between treatment a and b changes depending on whether male or female patients are being treated.

To do this analysis, we first need to split the dataset up into two groups, one dataset including only men and the other including only women. You can use the filter function that you’ve previously seen to separate out males and females into different data sets. Here, sex is categorized as 0 for male and 1 for female.

# Use "filter" to select only male patients

lesson4d_males <-

lesson4d %>%

filter(sex == 0)

# To confirm:

table(lesson4d_males$sex)##

## 0

## 294# Use "filter" to select only female patients

lesson4d_females <-

lesson4d %>%

filter(sex == 1)

# To confirm:

table(lesson4d_females$sex)##

## 1

## 106# Males (sex == 0)

epi.2by2(

table(

factor(lesson4d_males$group, levels = c(1, 0)),

factor(lesson4d_males$response, levels = c(1, 0))

)

)## Outcome+ Outcome- Total Inc risk *

## Exposure+ 54 84 138 39.13 (30.94 to 47.80)

## Exposure- 80 76 156 51.28 (43.16 to 59.35)

## Total 134 160 294 45.58 (39.79 to 51.46)

##

## Point estimates and 95% CIs:

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Inc risk ratio 0.76 (0.59, 0.99)

## Inc odds ratio 0.61 (0.38, 0.97)

## Attrib risk in the exposed * -12.15 (-23.46, -0.85)

## Attrib fraction in the exposed (%) -31.05 (-70.49, -1.65)

## Attrib risk in the population * -5.70 (-15.40, 3.99)

## Attrib fraction in the population (%) -12.51 (-15.34, -8.48)

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Uncorrected chi2 test that OR = 1: chi2(1) = 4.359 Pr>chi2 = 0.037

## Fisher exact test that OR = 1: Pr>chi2 = 0.046

## Wald confidence limits

## CI: confidence interval

## * Outcomes per 100 population units# Females (sex == 1)

epi.2by2(

table(

factor(lesson4d_females$group, levels = c(1, 0)),

factor(lesson4d_females$response, levels = c(1, 0))

)

)## Outcome+ Outcome- Total Inc risk *

## Exposure+ 27 35 62 43.55 (30.99 to 56.74)

## Exposure- 17 27 44 38.64 (24.36 to 54.50)

## Total 44 62 106 41.51 (32.02 to 51.49)

##

## Point estimates and 95% CIs:

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Inc risk ratio 1.13 (0.71, 1.80)

## Inc odds ratio 1.23 (0.56, 2.69)

## Attrib risk in the exposed * 4.91 (-14.04, 23.87)

## Attrib fraction in the exposed (%) 11.28 (-39.65, 45.23)

## Attrib risk in the population * 2.87 (-14.30, 20.05)

## Attrib fraction in the population (%) 6.92 (-5.86, 23.93)

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Uncorrected chi2 test that OR = 1: chi2(1) = 0.256 Pr>chi2 = 0.613

## Fisher exact test that OR = 1: Pr>chi2 = 0.691

## Wald confidence limits

## CI: confidence interval

## * Outcomes per 100 population unitsWhat you get is a statistically significant difference between treatment groups for men (many more respond on regimen a) but not women (actually a few more respond on regimen b). How to interpret this? In the literature, this might well be trumpeted as showing that though either regimen could be used for women, regimen a is better for men. My own view is that sub-group analyses are hypothesis generating not hypothesis testing. In particular, is there any reason to believe that response to chemotherapy might depend on sex? I don’t think there are any cases of this.

Testing age is a little more difficult as it is a continuous variable. One typical approach might be to create two sub-groups depending on the median. First, quantile(lesson4d$age, c(0.5), na.rm = TRUE) gives a median age of 43. So:

# Use "filter" again to select age

lesson4d_younger <-

lesson4d %>%

filter(age <= 42)

lesson4d_older <-

lesson4d %>%

filter(age > 42)

# Younger patients

epi.2by2(

table(

factor(lesson4d_younger$group, levels = c(1, 0)),

factor(lesson4d_younger$response, levels = c(1, 0))

)

)## Outcome+ Outcome- Total Inc risk *

## Exposure+ 44 52 96 45.83 (35.62 to 56.31)

## Exposure- 56 47 103 54.37 (44.26 to 64.22)

## Total 100 99 199 50.25 (43.10 to 57.40)

##

## Point estimates and 95% CIs:

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Inc risk ratio 0.84 (0.64, 1.12)

## Inc odds ratio 0.71 (0.41, 1.24)

## Attrib risk in the exposed * -8.54 (-22.39, 5.32)

## Attrib fraction in the exposed (%) -18.62 (-57.90, 10.12)

## Attrib risk in the population * -4.12 (-15.98, 7.75)

## Attrib fraction in the population (%) -8.19 (-11.88, -2.70)

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Uncorrected chi2 test that OR = 1: chi2(1) = 1.448 Pr>chi2 = 0.229

## Fisher exact test that OR = 1: Pr>chi2 = 0.258

## Wald confidence limits

## CI: confidence interval

## * Outcomes per 100 population units# Older patients

epi.2by2(

table(

factor(lesson4d_older$group, levels = c(1, 0)),

factor(lesson4d_older$response, levels = c(1, 0))

)

)## Outcome+ Outcome- Total Inc risk *

## Exposure+ 36 66 102 35.29 (26.09 to 45.38)

## Exposure- 41 56 97 42.27 (32.30 to 52.72)

## Total 77 122 199 38.69 (31.89 to 45.84)

##

## Point estimates and 95% CIs:

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Inc risk ratio 0.84 (0.59, 1.19)

## Inc odds ratio 0.75 (0.42, 1.32)

## Attrib risk in the exposed * -6.97 (-20.49, 6.54)

## Attrib fraction in the exposed (%) -19.76 (-70.41, 15.55)

## Attrib risk in the population * -3.57 (-15.51, 8.36)

## Attrib fraction in the population (%) -9.24 (-15.01, -1.29)

## -------------------------------------------------------------------

## Uncorrected chi2 test that OR = 1: chi2(1) = 1.019 Pr>chi2 = 0.313

## Fisher exact test that OR = 1: Pr>chi2 = 0.382

## Wald confidence limits

## CI: confidence interval

## * Outcomes per 100 population unitsYou get no difference between groups for either older or younger patients. As it turns out, this is not a very efficient method of testing for age differences. A better technique will be discussed in the class on regression.

Interaction or sub-group analysis?

There is a further problem here: we have one question (“do effects differ between men and women?”) and two p-values (one for men and one for women). What you really want is one p-value to answer one question. The correct statistical technique for looking at whether the effects of treatment differ between sub-groups is called interaction. We will look at this later in the course. In the meantime, if you are interested, you can read some brief articles at:

Statistics Notes: Interaction 1: heterogeneity of effects

Statistics Notes: Interaction 2: compare effect sizes not p-values

Statistics Notes: Interaction 3: How to examine heterogeneity

9.4.5 lesson4e

This is a lab study of two candidate tumor-suppressor genes (gene1 and gene2). Wild-type mice are compared with mice that have gene1 knocked-out, gene2 knocked-out or both. The presence of tumors is measured after 30 days. Do the genes suppress cancer?

The obvious thing to do would be to use epi.2by2 with “cancer” and “gene1”, and then with “cancer” and “gene2”. Superficially this would suggest that gene1 is a tumor suppressor gene and gene2 is not. However, don’t get too fixated on p-values. The proportion of cancer in mice with gene2 knocked out is over twice that of controls. Remember that animal experiments tend to use a very small number of observations (a typical clinical trial has hundreds of patients, a typical lab study has maybe a dozen mice). So you might want to say that there is good evidence that gene1 is a tumor suppressor gene but that whilst evidence is suggestive for gene2, more research is needed.

A BIG HOWEVER - have a look at the data or this table:

# Formatted table of gene1 by gene2

tbl_summary(

lesson4e %>% select(gene1, gene2),

by = gene2,

type = list(gene1 = "categorical")

)| Characteristic | 0 N = 121 |

1 N = 121 |

|---|---|---|

| gene1 | ||

| 0 | 6 (50%) | 6 (50%) |

| 1 | 6 (50%) | 6 (50%) |

| 1 n (%) | ||

The experimental design was to knockout no genes in some animals, gene1 in some animals, gene2 in other animals and both genes in a final set of animals. This is known as a factorial or Latin-square design. Analyzing rates of cancer for mice without gene1 or gene2, as suggested above, ignores this experimental design. Presumably the design was implemented because the researchers wanted to know if the effects of gene1 differed depending on whether gene2 had been knocked-out and vice versa. Now you could start doing separate sub-groups (e.g. using epi.2by2 for “cancer” and “gene1”, filtering by “gene2==0” and “gene2==1” separately) but this produces somewhat unhelpful results. For example, it suggests that gene1 has an effect for wild-type gene2 (p=0.046) but maybe not for knocked out gene2 (p=0.079). This has all the look and feel of a spurious sub-group analysis, however. We will discuss some regression approaches to this problem later in the lecture series.

9.5 Week 5

# Week 5: load packages

library(skimr)

library(gt)

library(gtsummary)

library(epiR)

library(broom)

library(pROC)

library(gmodels)

library(survival)

library(here)

library(tidyverse)

# Week 5: load data

lesson5a <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5a.rds"))

lesson5b <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5b.rds"))

lesson5c <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5c.rds"))

lesson5d <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5d.rds"))

lesson5e <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5e.rds"))

lesson5f <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5f.rds"))

lesson5g <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5g.rds"))

lesson5h <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5h.rds"))

lesson5i <- readRDS(here::here("Data", "Week 5", "lesson5i.rds"))9.5.1 lesson5a

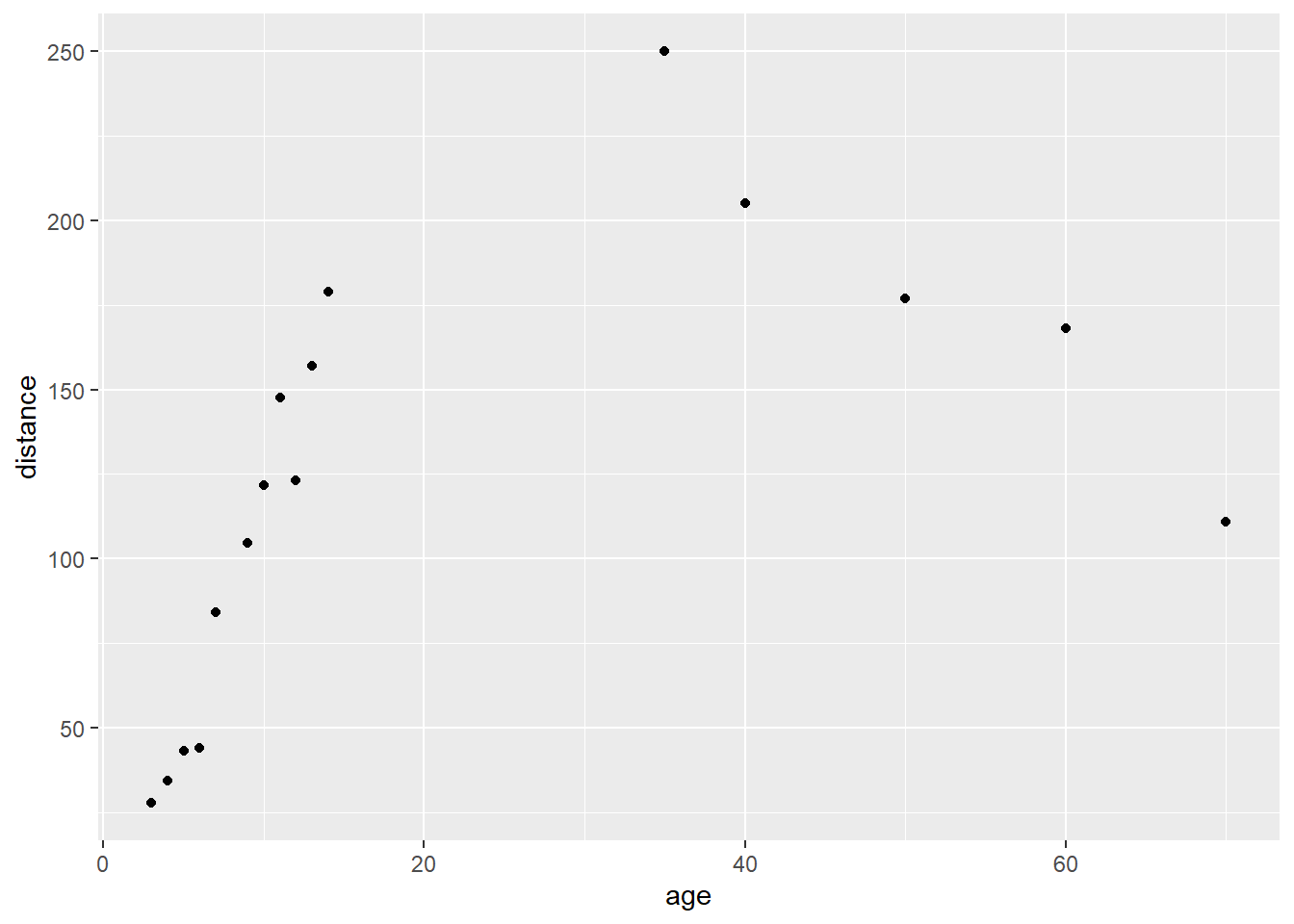

These are data from marathon runners (again). Which of the following is associated with how fast runners complete the marathon: age, sex, training miles, weight?

My guess here is that we are going to want to do a regression analysis. This would allow us to quantify the association between the various predictor variables and race time. For example, it would be interesting to know not only that number of weekly training miles is correlated with race time, but by how much you can reduce your race time if you increased your training by a certain amount. Our dependent variable is “rt” (race time in minutes), so we could type:

# Create linear regression model for race time

rt_model <- lm(rt ~ age + sex + tr + wt, data = lesson5a)

# Results of linear regression model

summary(rt_model)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = rt ~ age + sex + tr + wt, data = lesson5a)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -100.066 -26.311 -3.977 20.682 165.336

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 256.48412 18.29679 14.018 < 2e-16 ***

## age 0.80819 0.25451 3.175 0.001719 **

## sex 23.16076 6.02247 3.846 0.000159 ***

## tr -1.48529 0.20717 -7.169 1.23e-11 ***

## wt 0.04766 0.17133 0.278 0.781145

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 39.36 on 212 degrees of freedom

## (45 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.2605, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2465

## F-statistic: 18.67 on 4 and 212 DF, p-value: 3.677e-13The p-values for all the predictor variables apart from weight are very low. A model answer might be:

There were 262 runners in the dataset; full data were available for 217. Summary data for these 217 are given in table 1. Predictors of race time are shown in table 2. Age, sex and number of training miles were all statistically significant predictors of race time; weight is unlikely to have an important effect.

| Characteristic | N = 2171 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42 (11) |

| Female | 61 (28%) |

| Training miles per week | 36 (13) |

| Race time (minutes) | 246 (45) |

| Weight (kg) | 76 (16) |

| 1 Mean (SD); n (%) | |

| Characteristic | Beta | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.81 | 0.31, 1.3 | 0.002 |

| Female | 23 | 11, 35 | <0.001 |

| Training miles per week | -1.5 | -1.9, -1.1 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 0.05 | -0.29, 0.39 | 0.8 |

| Abbreviation: CI = Confidence Interval | |||

A real-life decision you could take away from this is that every additional mile you run in training would be predicted to cut about 1.5 minutes from your marathon time: add a couple of extra five mile runs per week and you’ll shave a quarter of an hour off your time.

A couple of thoughts. First, you will note that I didn’t remove weight from the model (that is, use a step wise approach) then report the coefficients and p-values for the new model (by typing lm(rt ~ age + sex + tr, data = lesson5a)).

Second, race time is not normally distributed and the textbooks would have us believe that this invalidates a regression analysis. Let’s try:

# Create variable for log of race time

lesson5a <-

lesson5a %>%

mutate(

lt = log(rt)

)

# Create linear regression model for log of race time

rtlog_model <- lm(lt ~ age + sex + tr + wt, data = lesson5a)

# Results of linear regression model

summary(rtlog_model)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = lt ~ age + sex + tr + wt, data = lesson5a)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.44858 -0.10750 -0.00080 0.09165 0.58183

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 5.5305274 0.0729321 75.831 < 2e-16 ***

## age 0.0033135 0.0010145 3.266 0.00127 **

## sex 0.0980829 0.0240060 4.086 6.23e-05 ***

## tr -0.0063758 0.0008258 -7.721 4.51e-13 ***

## wt 0.0003336 0.0006829 0.488 0.62570

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.1569 on 212 degrees of freedom

## (45 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.2893, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2759

## F-statistic: 21.58 on 4 and 212 DF, p-value: 5.978e-15This creates a new variable called “lt” that is the log of race time. You can use the skim function to see that it is normally distributed. Now let’s look at the results of the regression analysis: the p-values are almost exactly the same. This suggests that the non-normality of race time is not important in this setting.

For advanced students only

It might be interesting to compare the coefficients from the untransformed and log transformed models. For example, women are predicted to run about 23 minutes slower on the untransformed model; the coefficient in the log model is 0.098. Backtransform by typing exp(0.098) and you get 1.10. Remember that backtransforming gives you a proportion. So to work out the difference between men and women in race time, first work out the average men’s time:

| Name | Piped data |

| Number of rows | 190 |

| Number of columns | 6 |

| _______________________ | |

| Column type frequency: | |

| numeric | 1 |

| ________________________ | |

| Group variables | None |

Variable type: numeric

| skim_variable | n_missing | complete_rate | mean | sd | p0 | p25 | p50 | p75 | p100 | hist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rt | 1 | 0.99 | 238.57 | 46.63 | 155 | 205 | 235 | 268 | 414 | ▅▇▃▁▁ |

Then multiply the men’s average (238.6) by 1.10 to get the women’s time, which gives 263.2.

Subtract one from the other to get 24.6 minutes difference in race time between the sexes. This is very close to the value from the untransformed model.

9.5.2 lesson5b

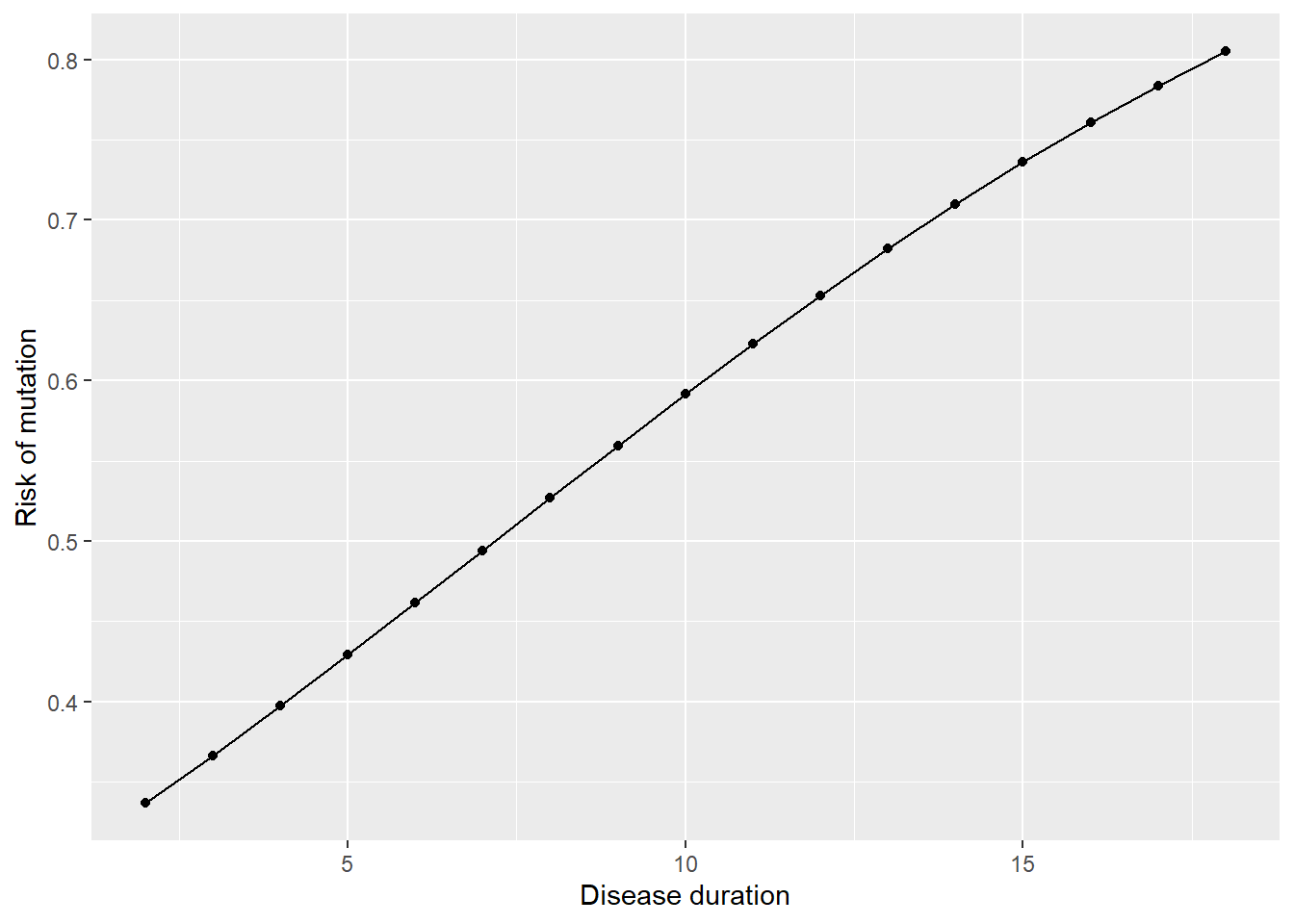

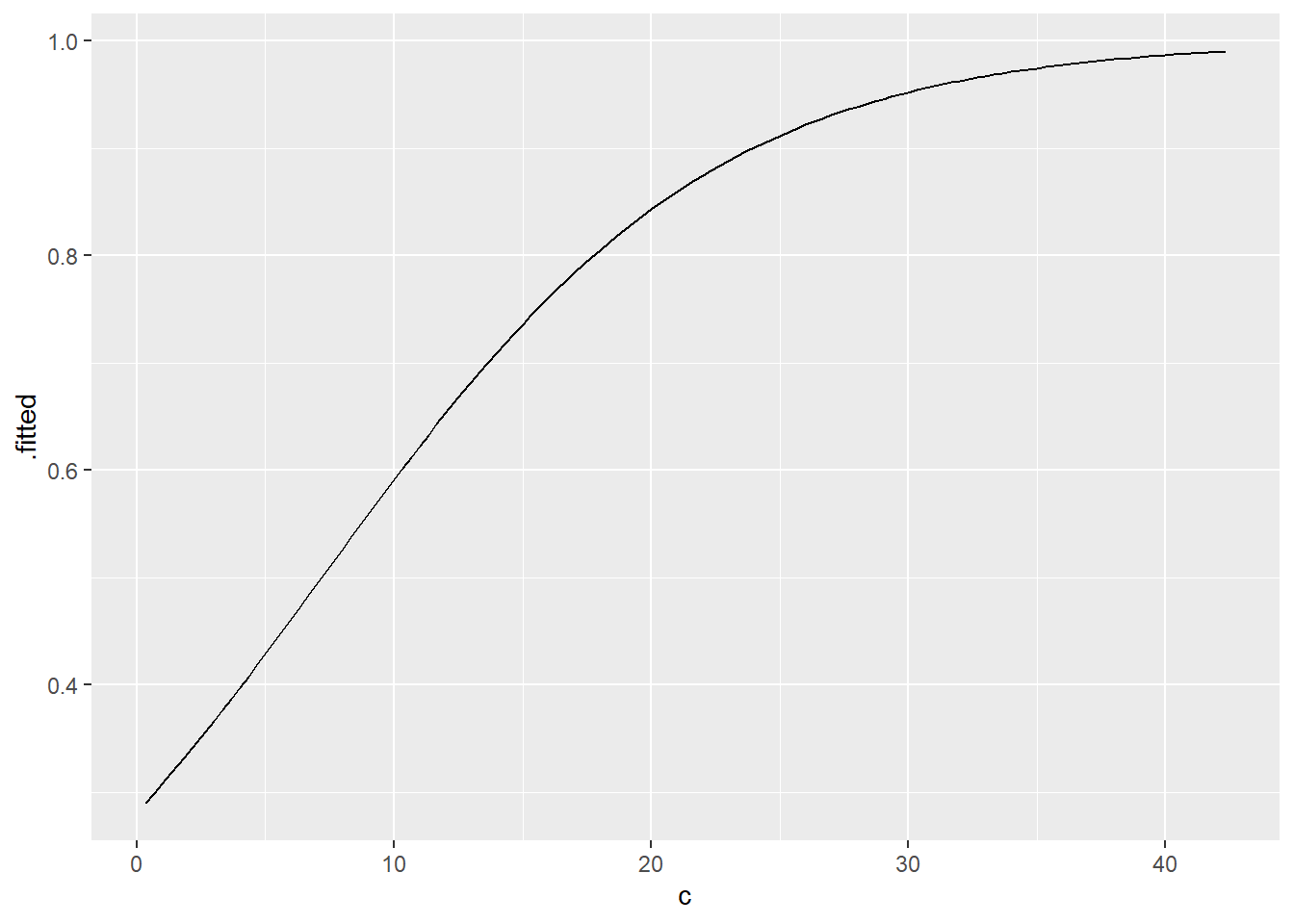

These are data on patients with a disease that predisposes them to cancer. The disease causes precancerous lesions that can be surgically removed. A group of recently removed lesions are analyzed for a specific mutation. Does how long a patient has had the disease affect the chance that a new lesion will have a mutation?

What you are trying to predict here is binary (mutation / no mutation). You are predicting with a continuous variable (length of disease). So a logistic regression would work nicely. Try:

# Create logistic regression model

mutate_model <- glm(mutation ~ c, data = lesson5b, family = "binomial")

# Formatted results with odds ratios

tbl_regression(mutate_model, exponentiate = TRUE)| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| c | 0.99 | 0.96, 1.02 | 0.7 |

| Abbreviations: CI = Confidence Interval, OR = Odds Ratio | |||

If you get a p-value of around 0.7, you haven’t been inspecting your data. One patient has apparently had the disease for 154 years. Either this is a freak of nature or the study assistant meant to type 14 or 15. You need to delete this observation from the dataset and try the model again:

# Use "filter" to exclude patients with outlying disease duration

lesson5b <-

lesson5b %>%

filter(c <= 50)

# Create logistic regression model

mutate_model <- glm(mutation ~ c, data = lesson5b, family = "binomial")

# Formatted results with odds ratios

tbl_regression(mutate_model, exponentiate = TRUE)| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

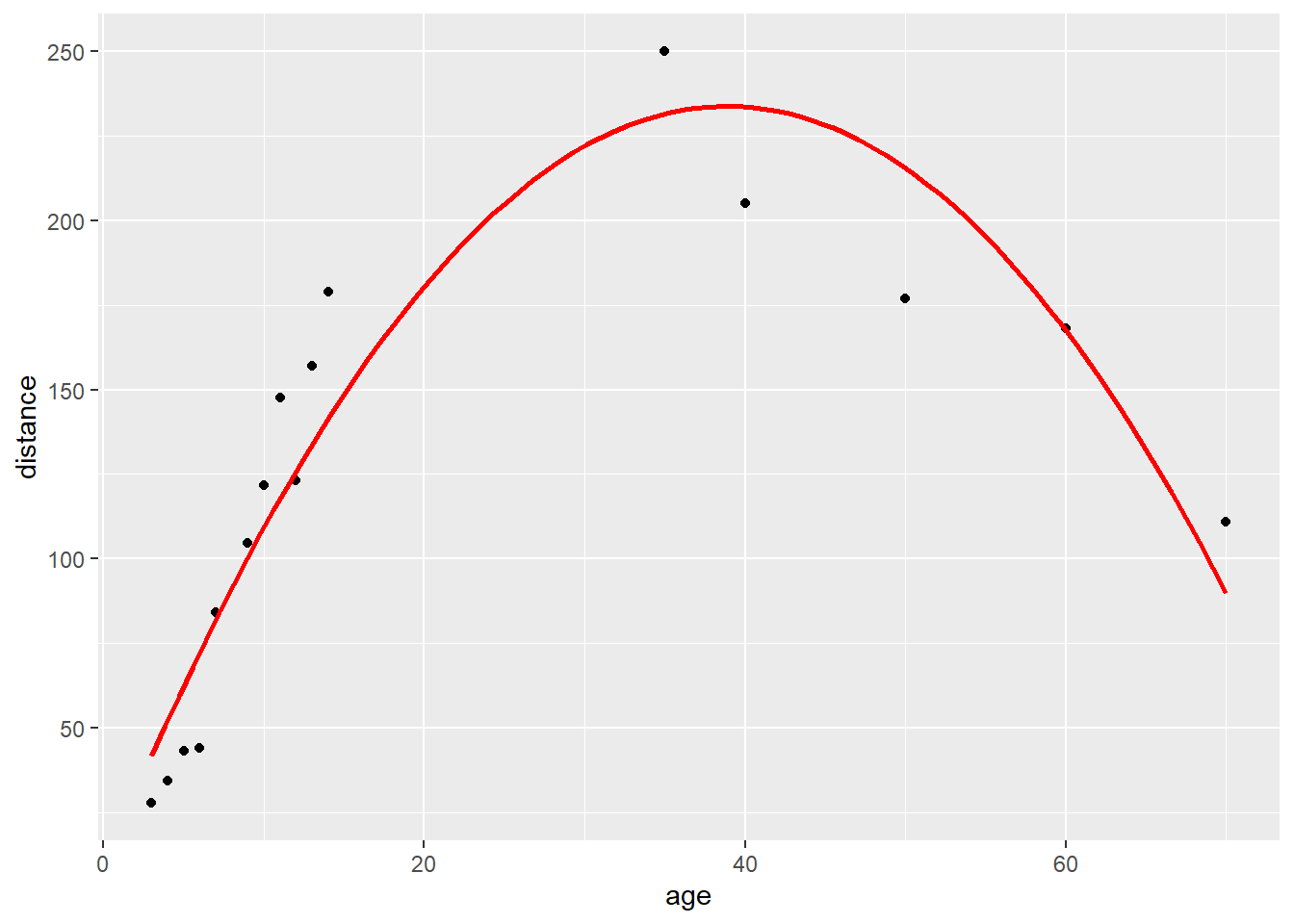

| c | 1.14 | 1.03, 1.27 | 0.014 |